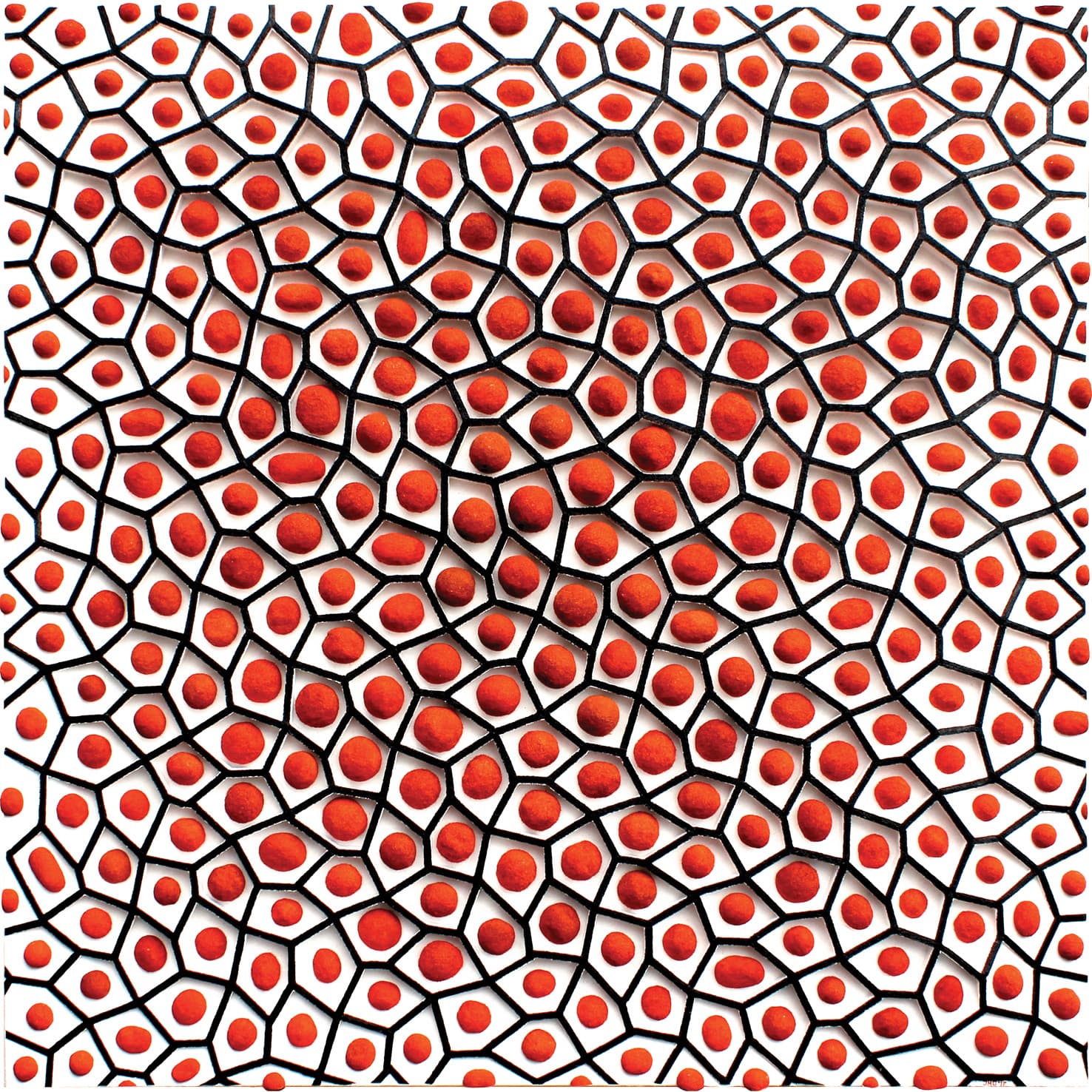

Souvenir de Roustchouk à la Asmat

2024

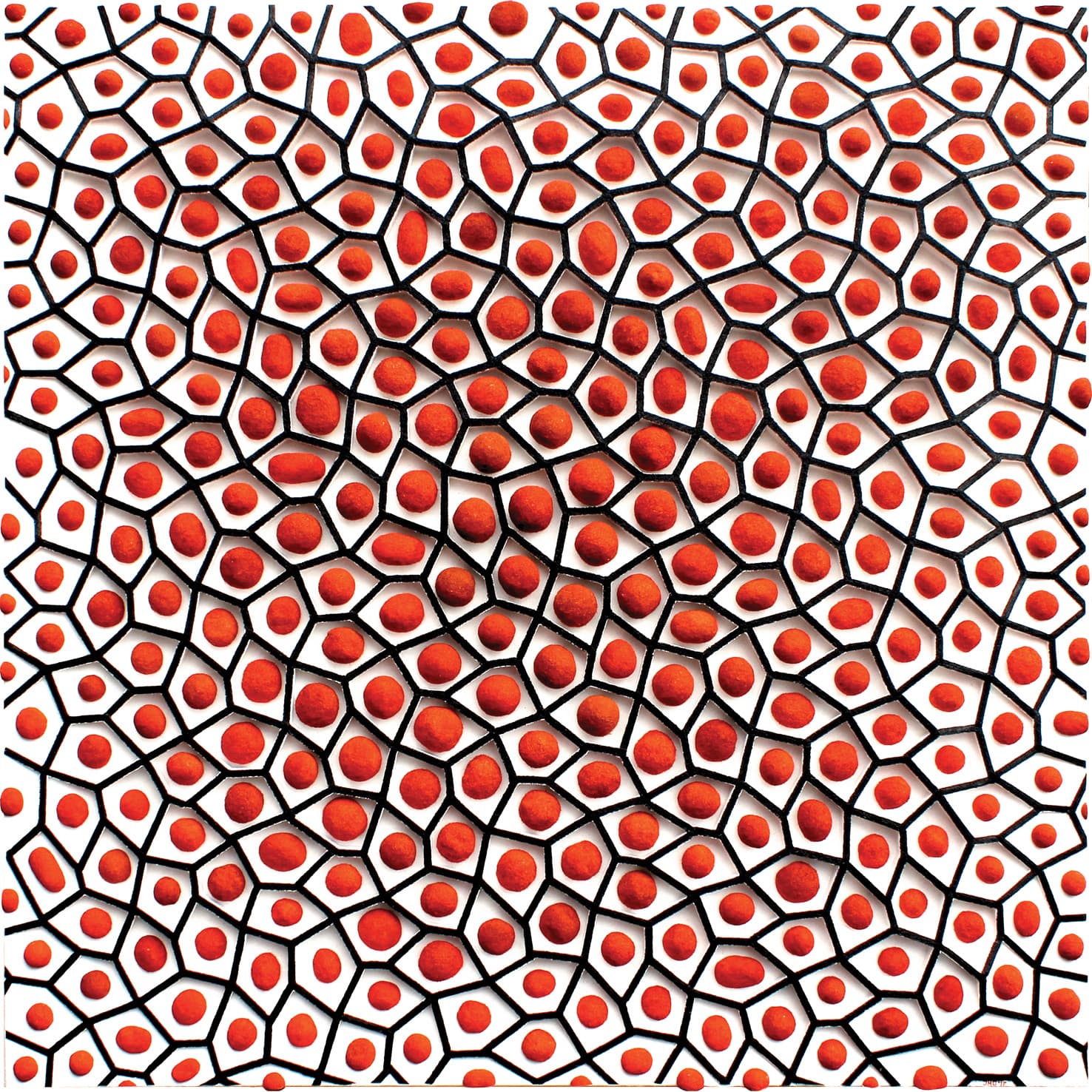

Souvenir pentagonale de Roustchouk

2024

Composition 2024

2024

Composition 2025

2025

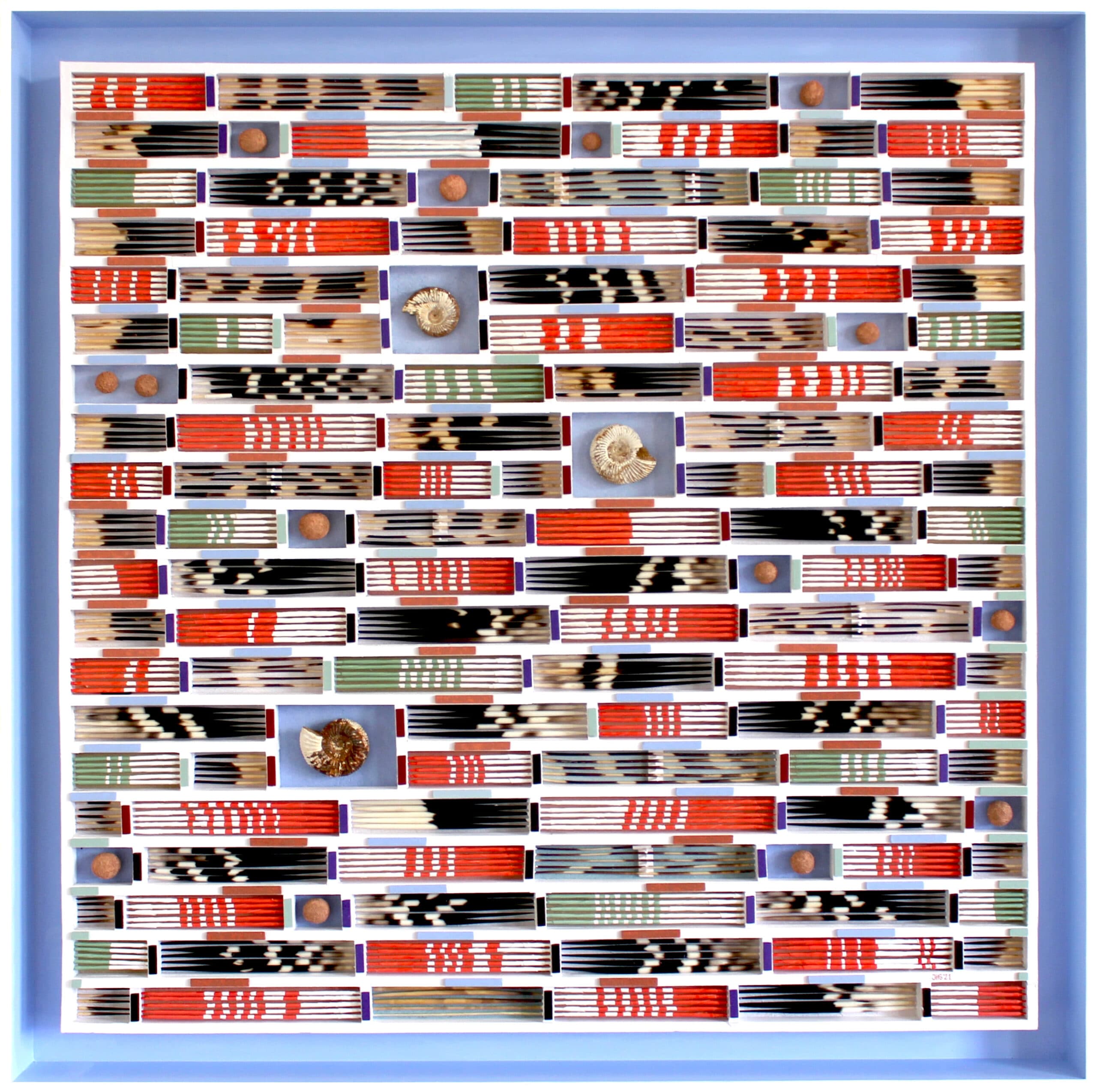

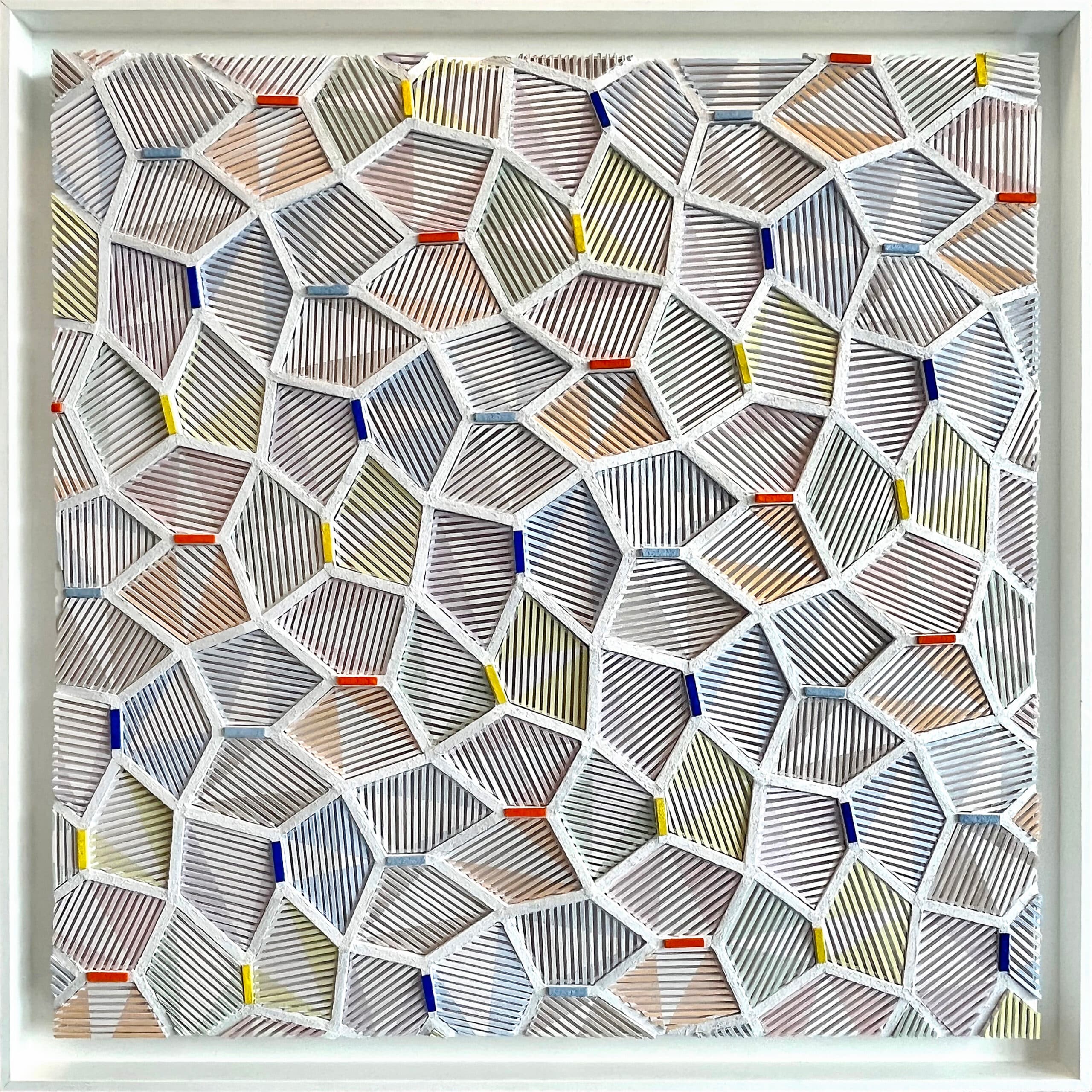

Porcupine I

2021

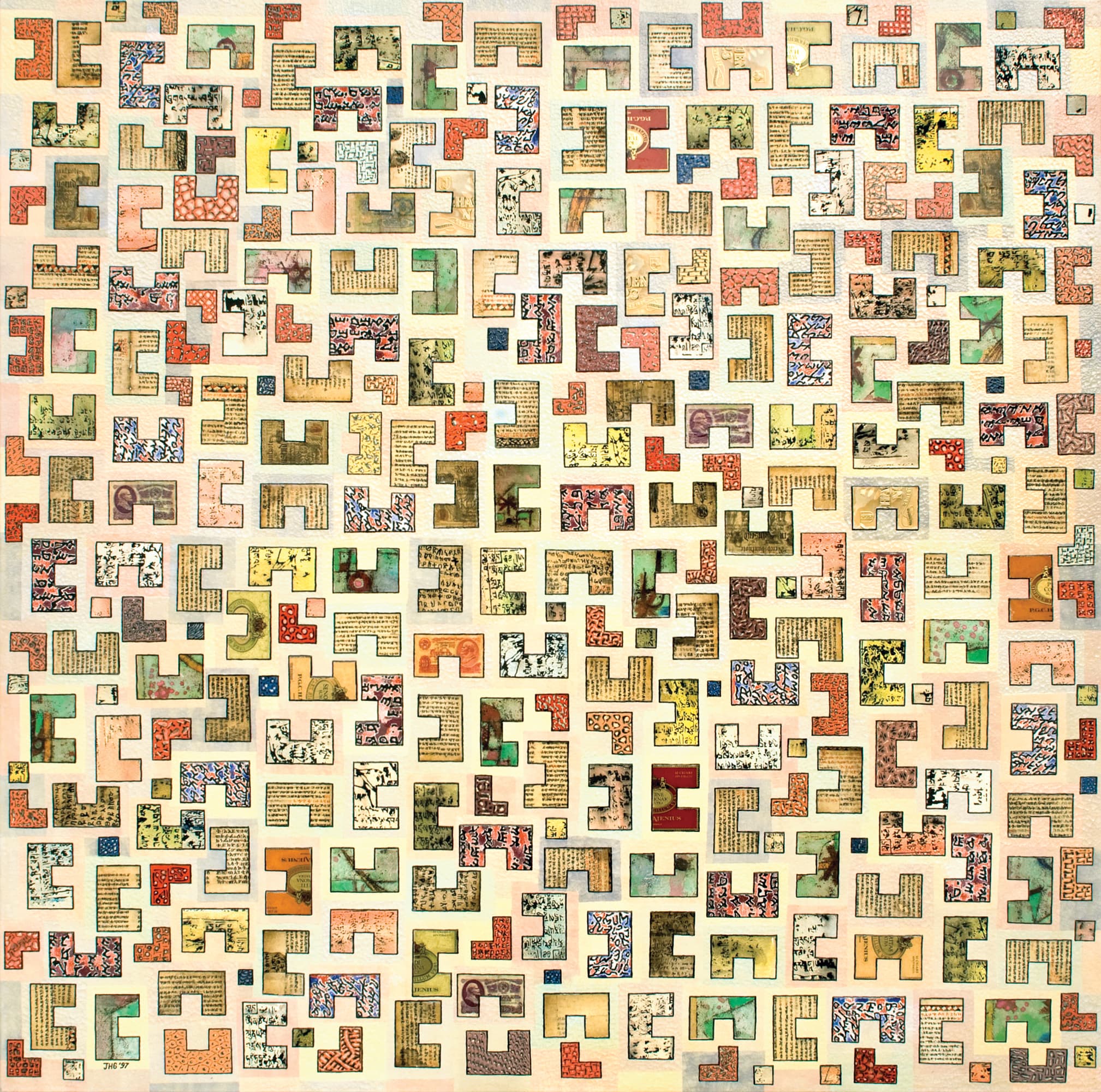

Division of the plane with various elements

1997

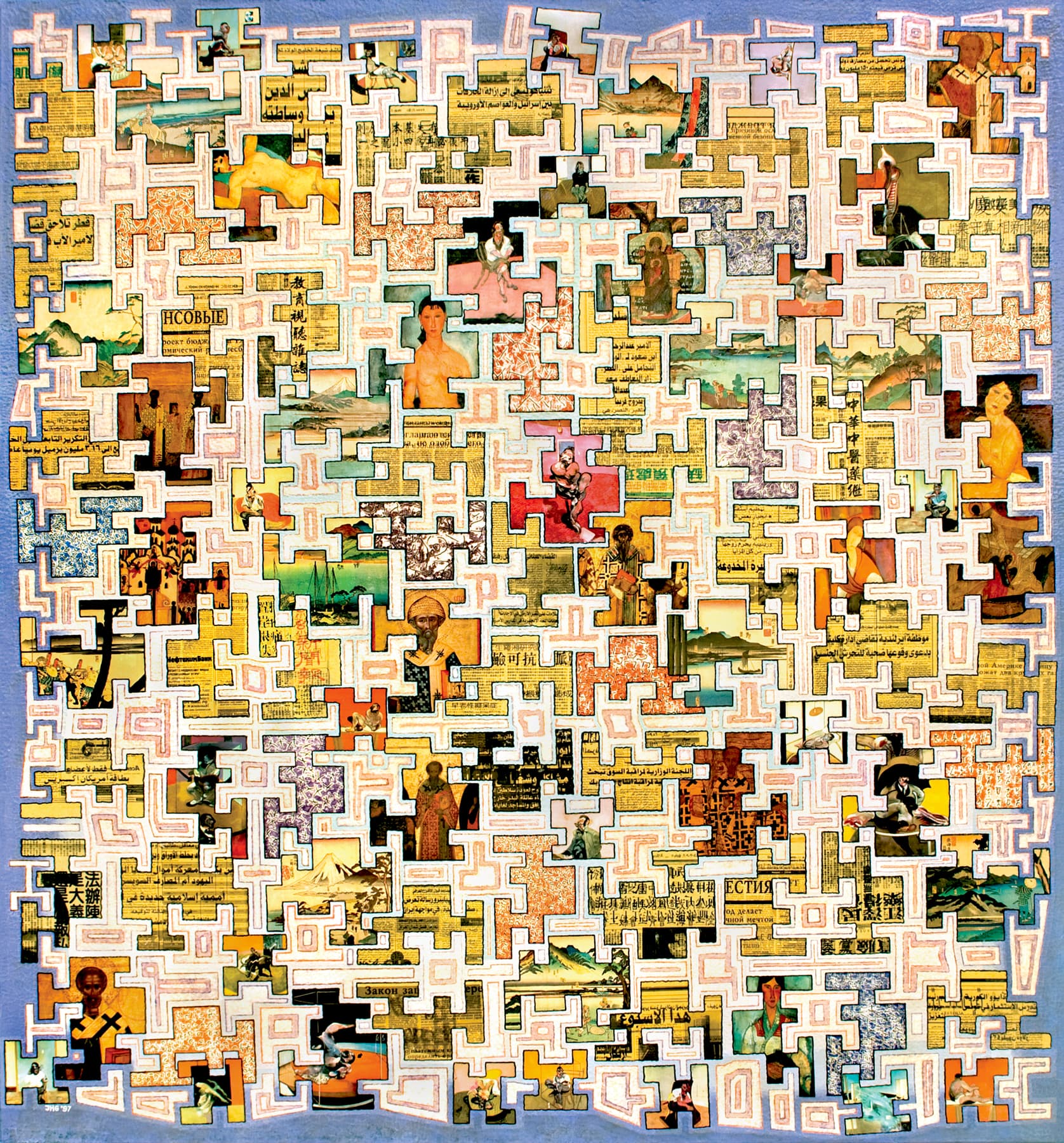

Disconnected tiling old and modern

1997

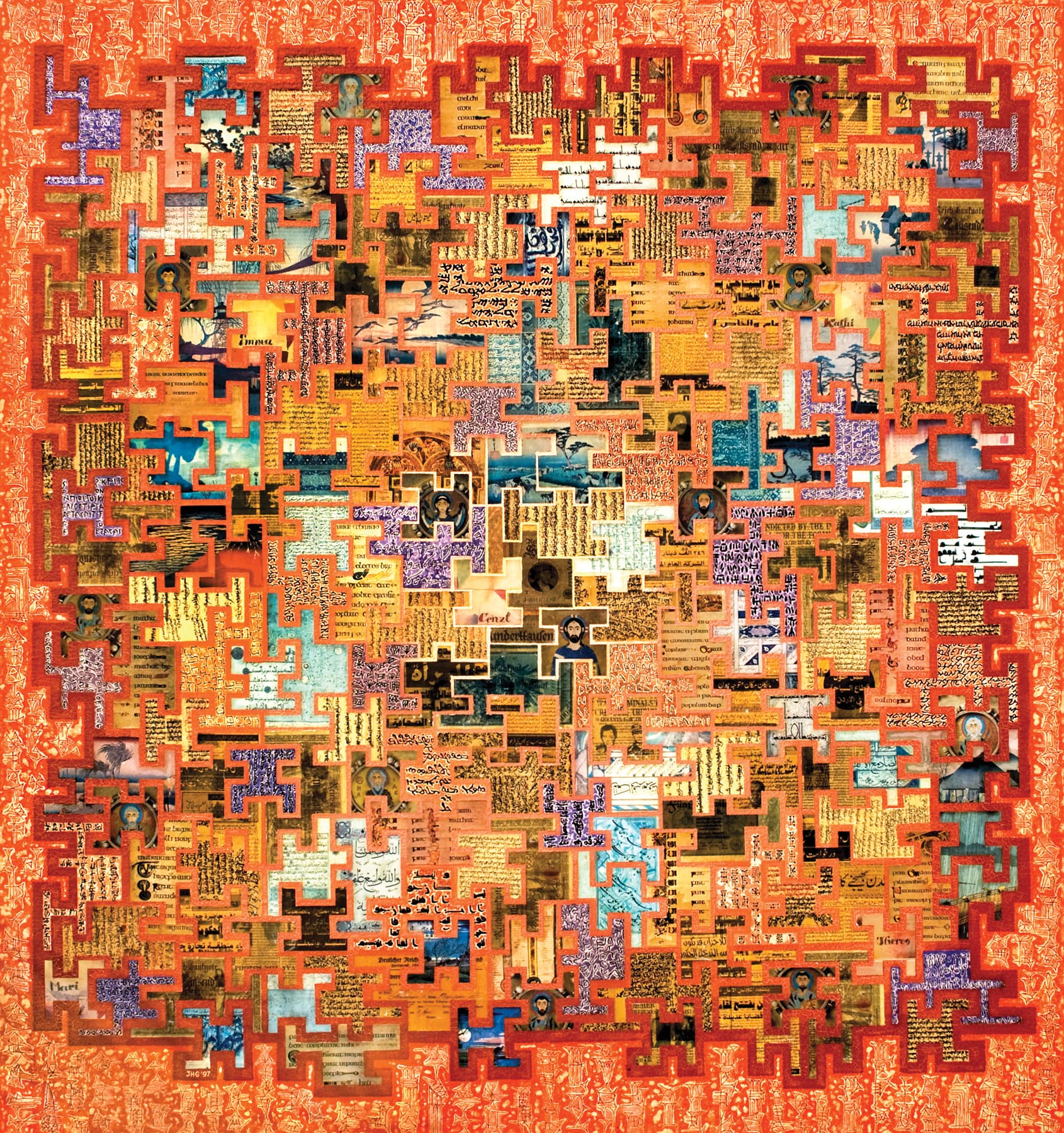

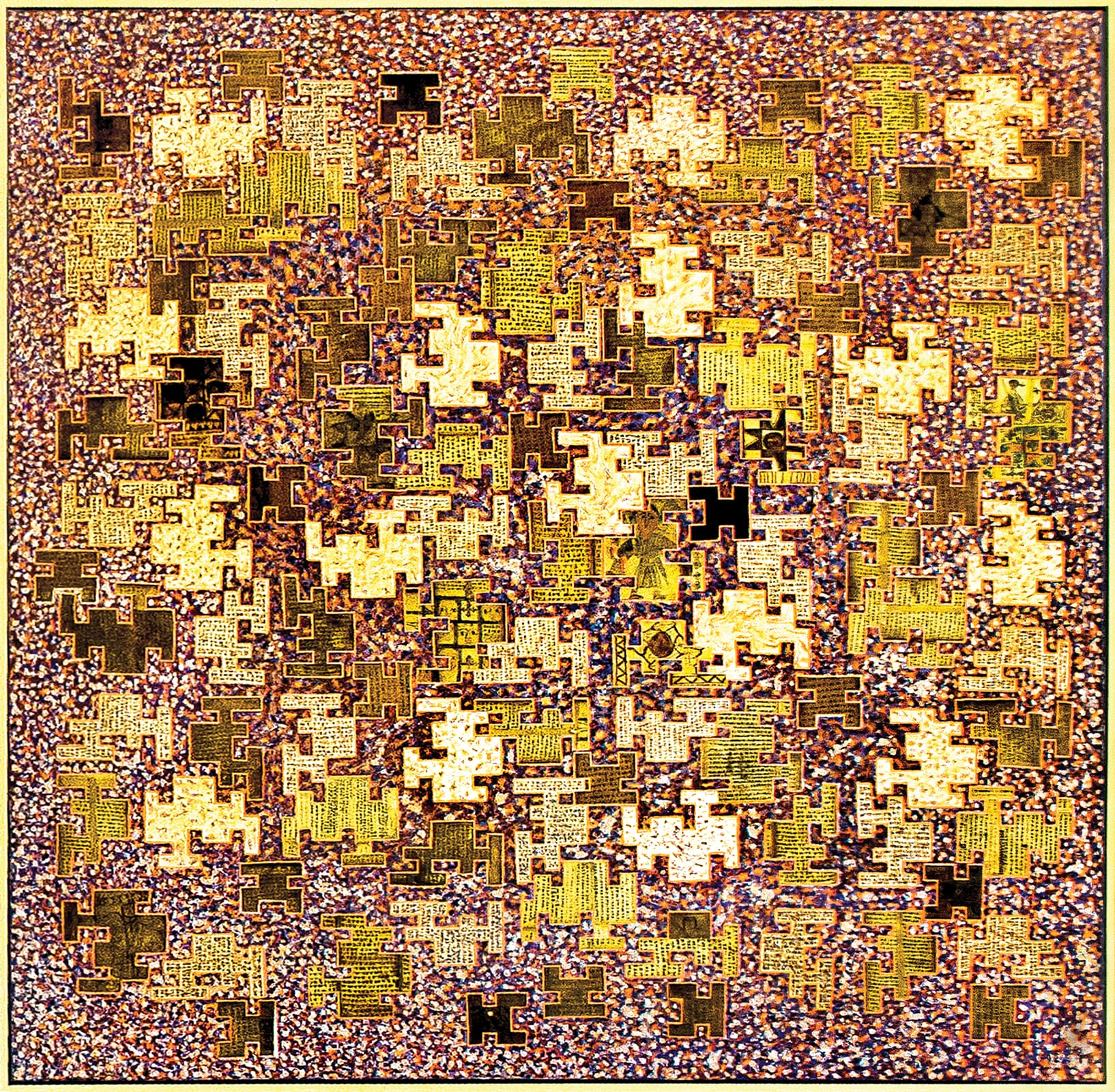

Tiling with handwritings

1997

Changing pattern with opening

1990

%202012%2C%2040%20x%2050%20cm.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Cepir-344 . Russian stock paper 1906

2012

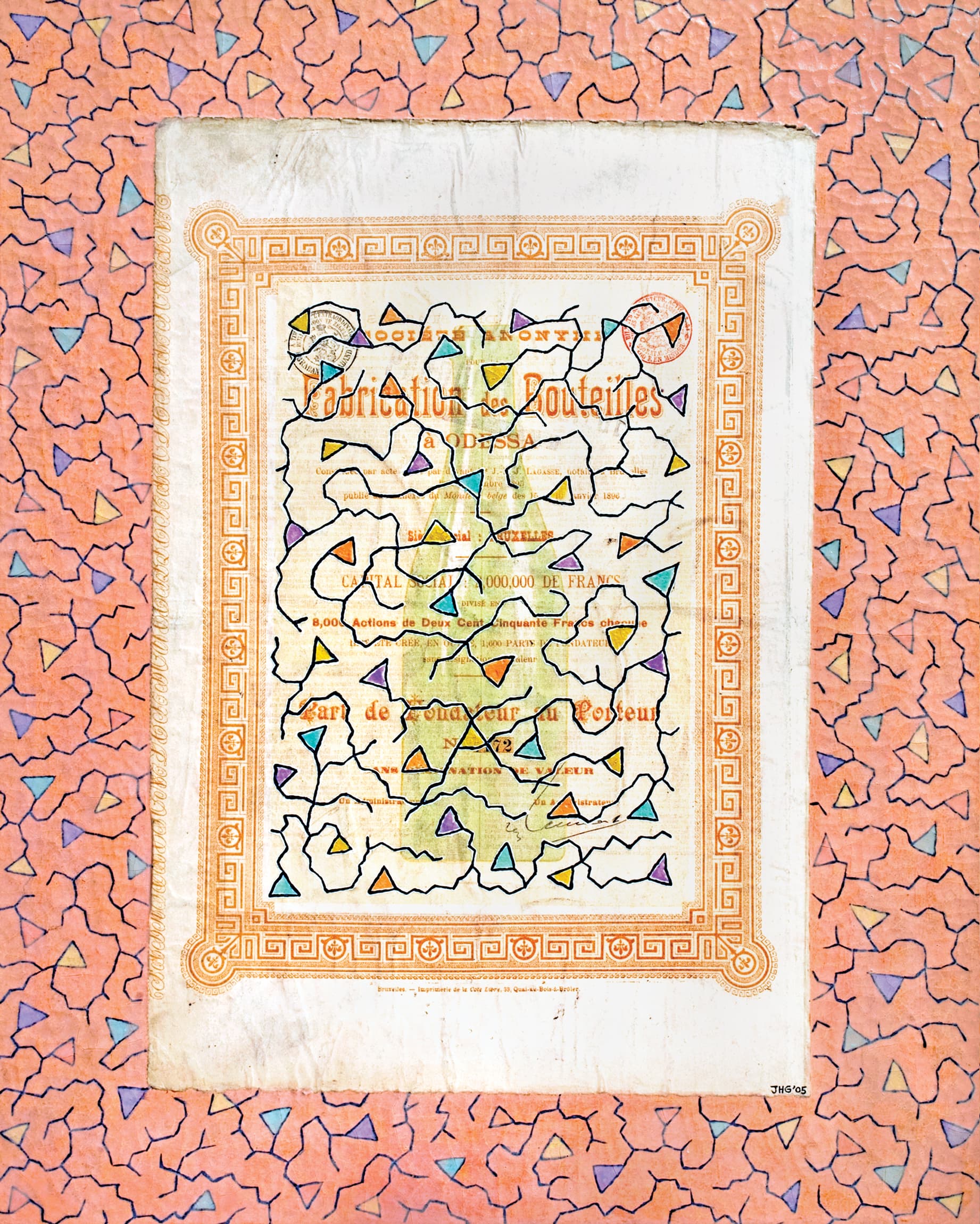

Fabrication des Bouteilles à Odessa I

2005

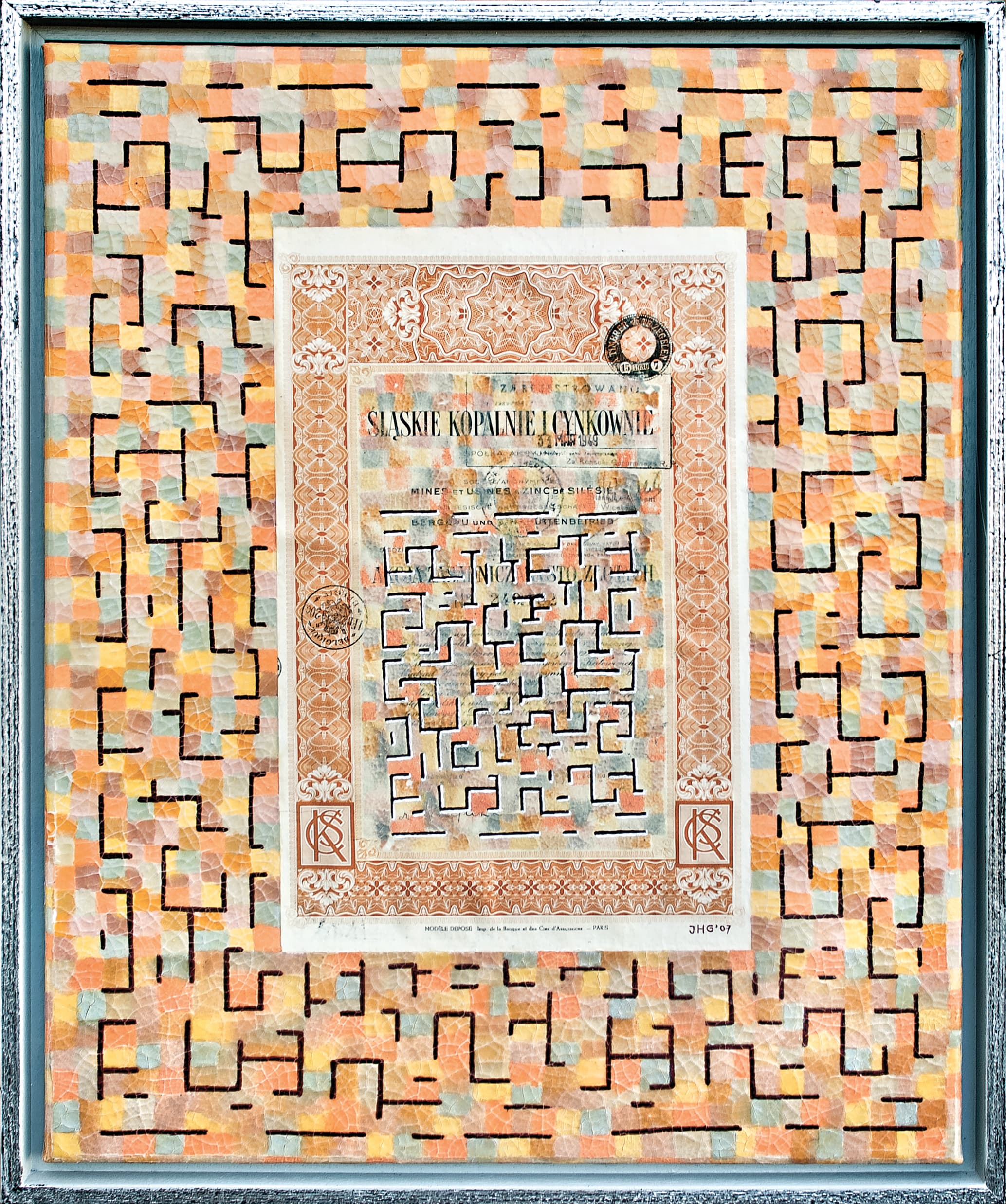

Mines et Usines Zinc de Silésie

2007

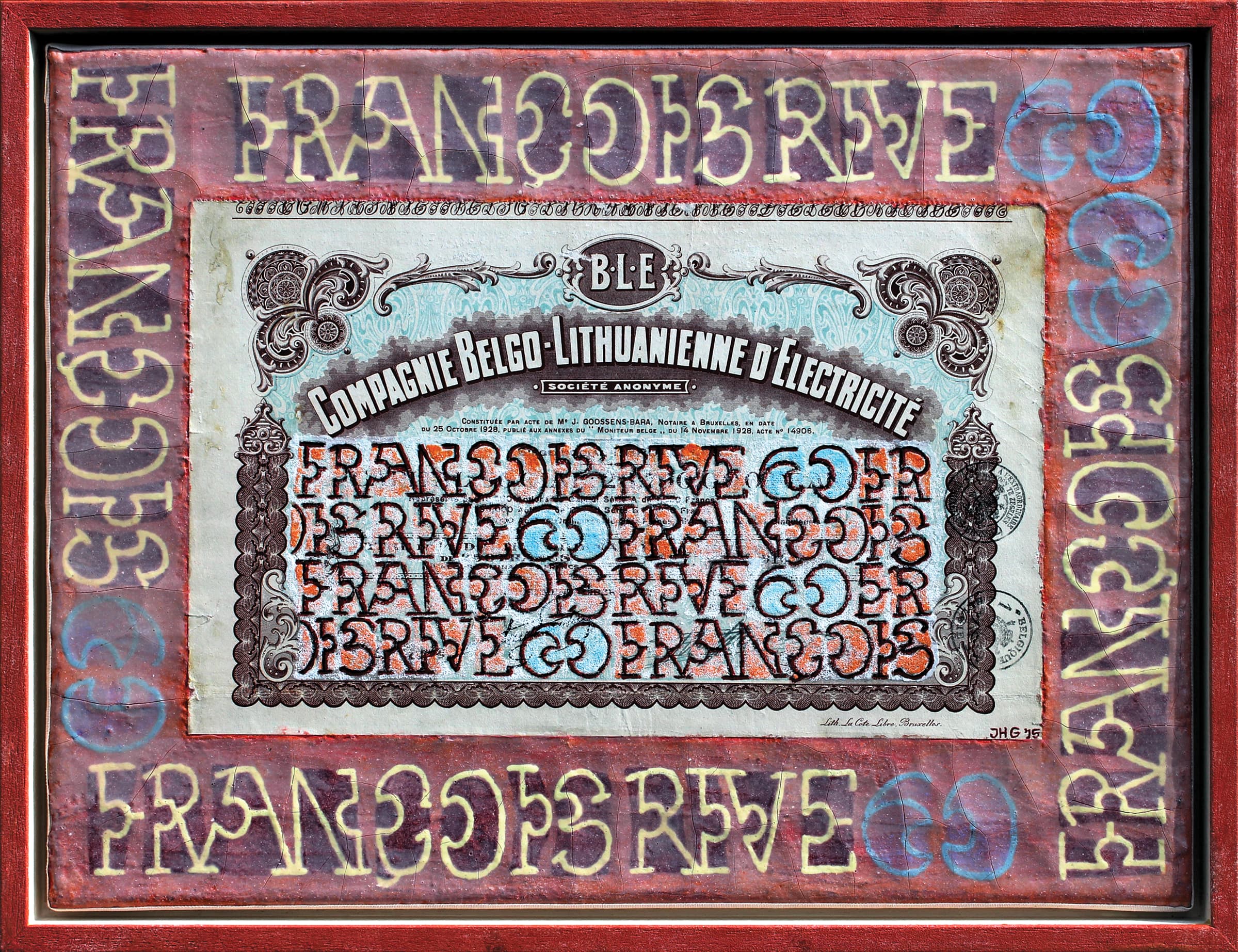

François Rive 60

2015

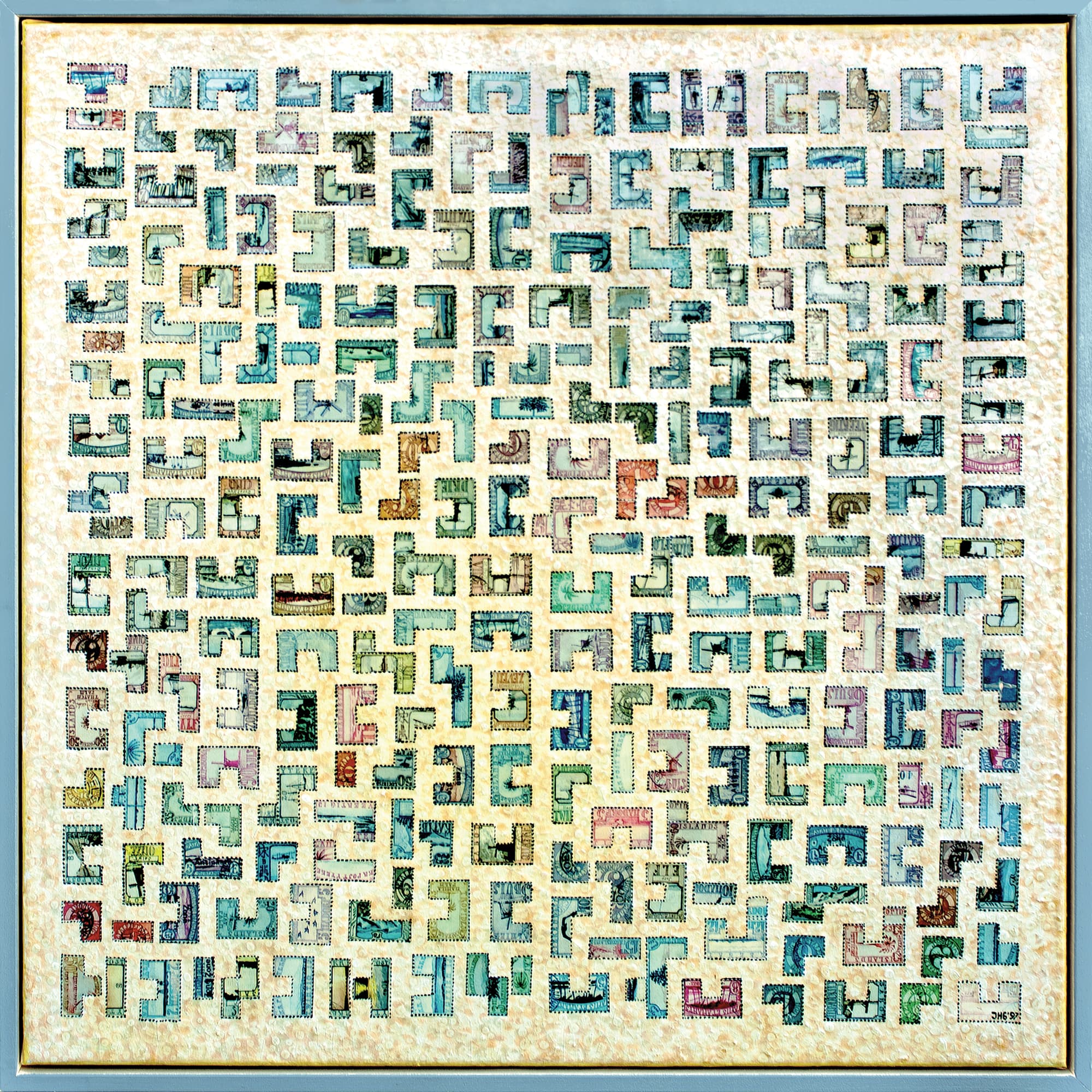

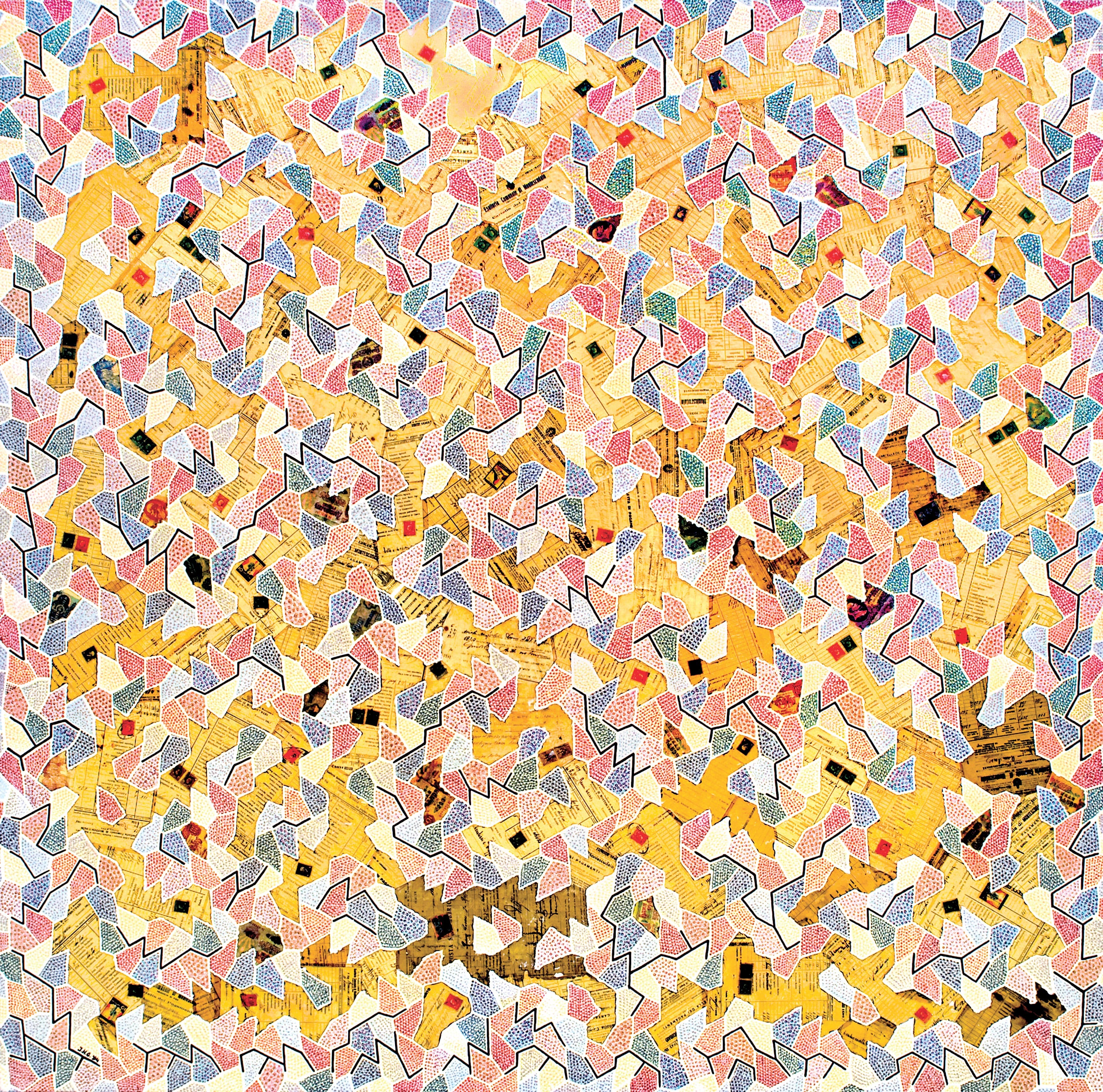

Division of the plane with stamps

1997

Disconnected Coptic tiling

1996

Tuscan tiling I

1994

Two worlds

1993

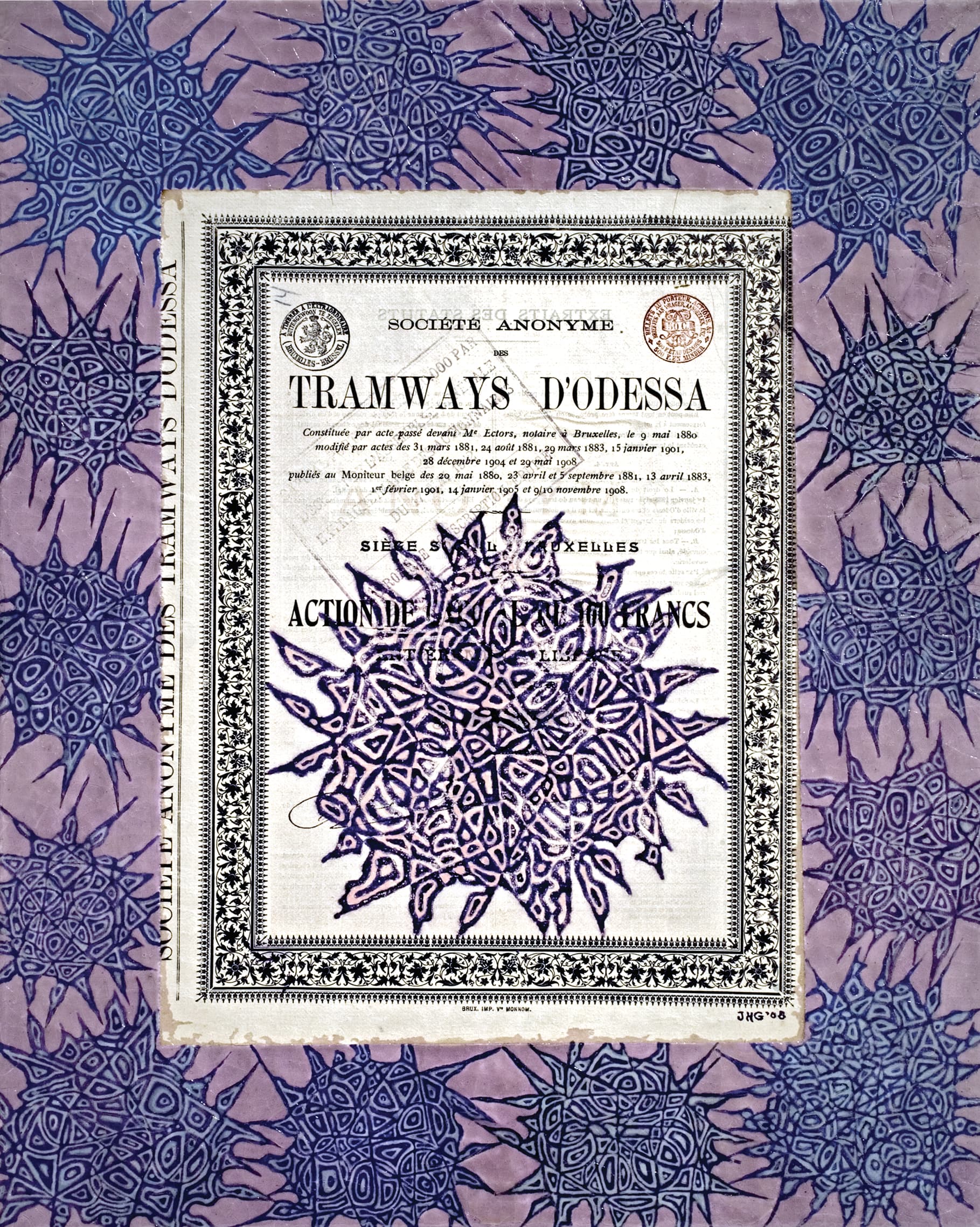

Tramways d'Odessa II

2008

Composition No.2

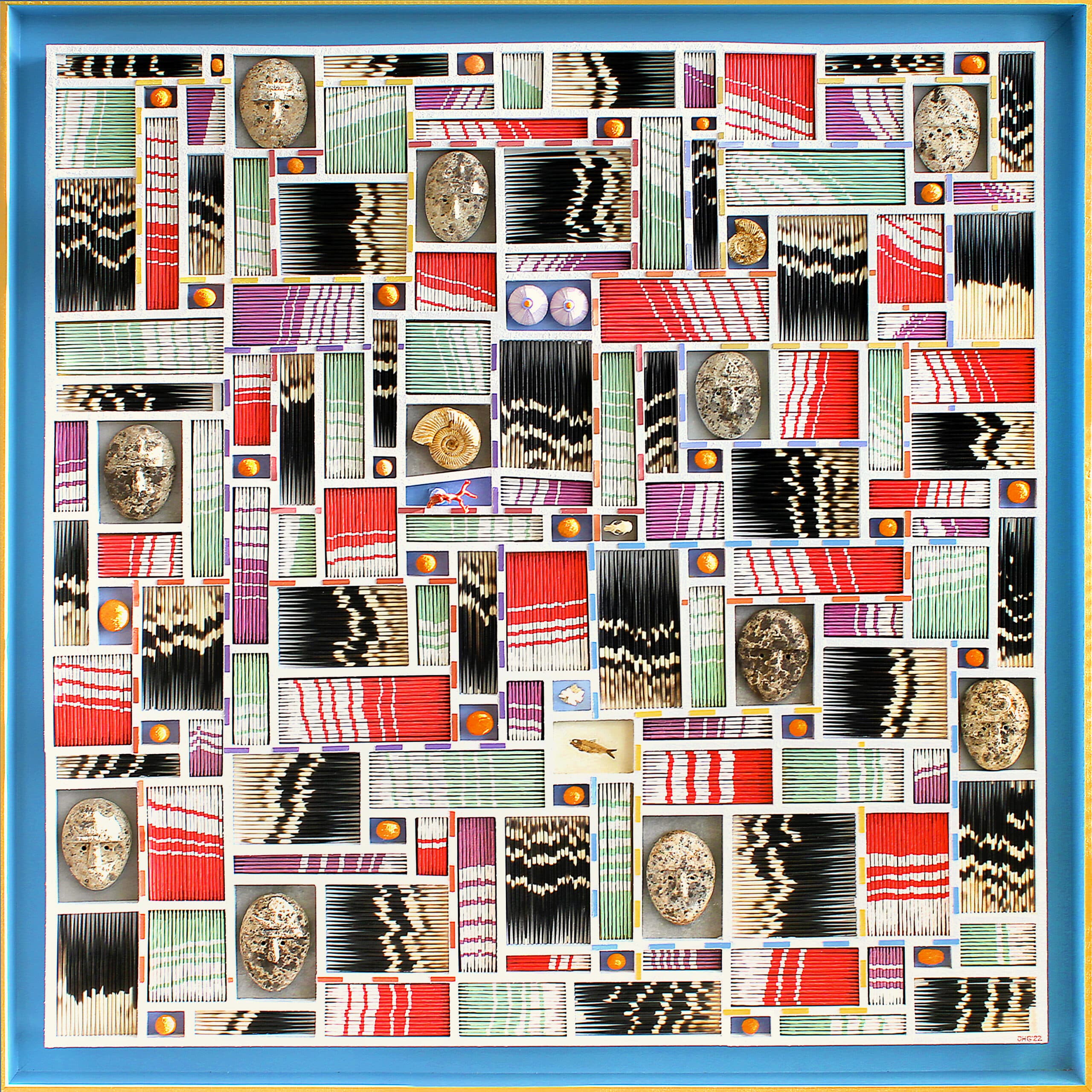

2022

Composition 2017

2017

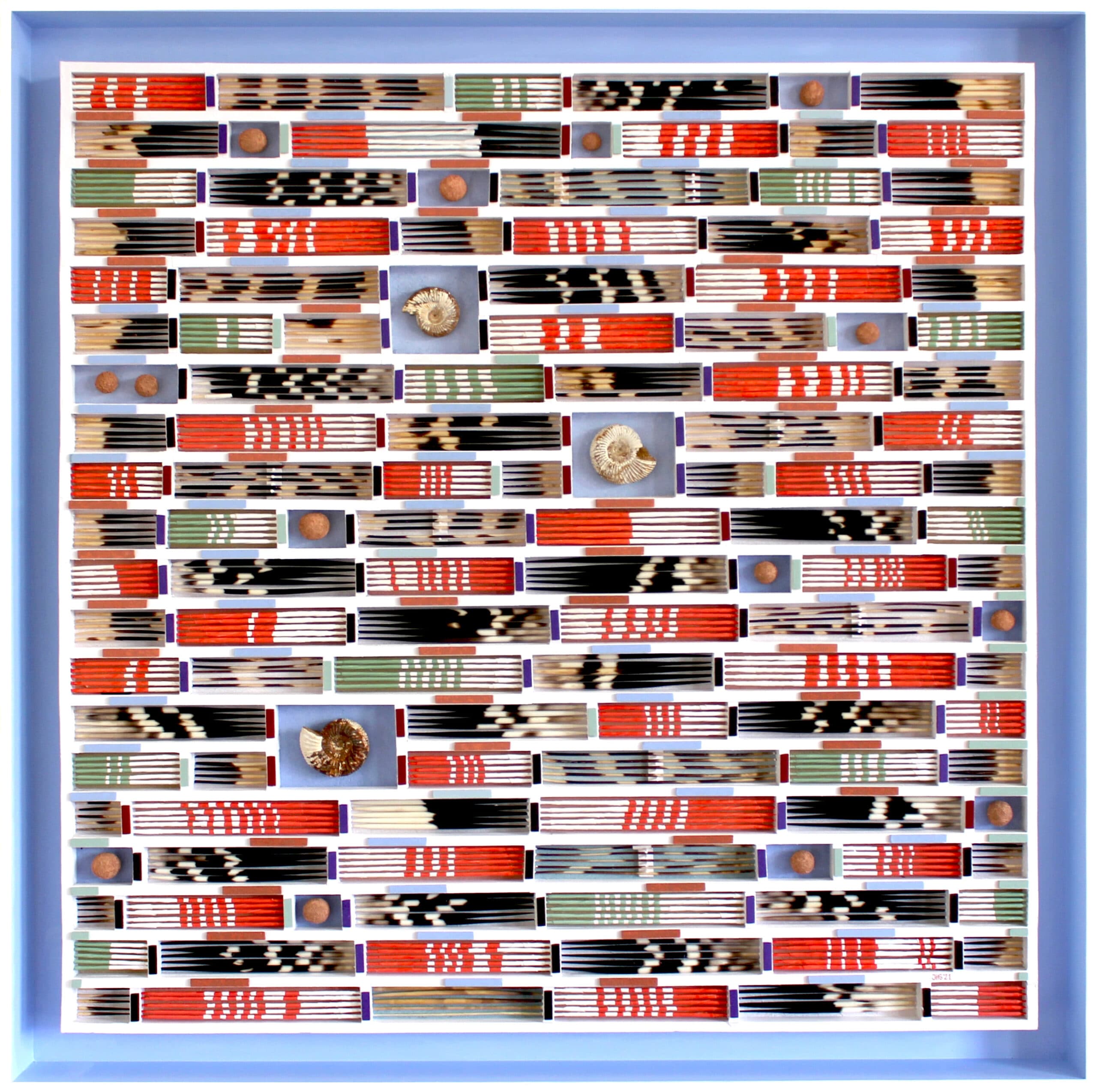

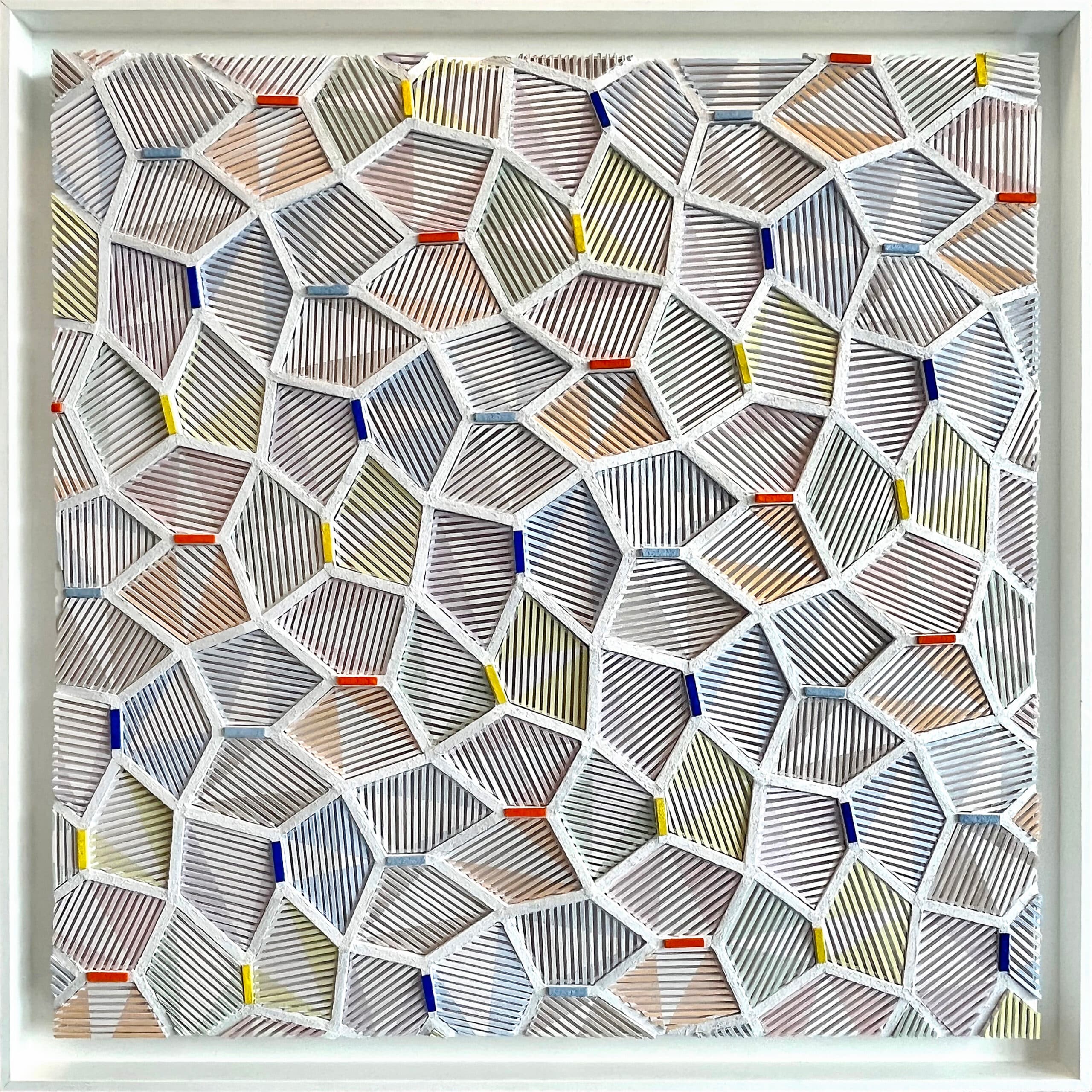

Porcupine Boogie Woogie II

2022

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Composition 2014

2014

Selected Works

Composition 2017

2017

A large-scale abstract composition with harmonious geometry and natural materials

Porcupine Artworks

2021

A series of works using porcupine quills as the primary medium

Composition No.2 - 2022

2022

A sophisticated geometric composition with bold colors

About the Artist

Jaap Goedemoed is an Amsterdam-based artist known for his distinctive geometric abstractions and innovative use of materials. His works explore mathematical patterns, particularly pentagonal tessellations, creating intricate structures that balance precision with artistic intuition.

With influences from ethnographic art and modernist traditions, Goedemoed creates compositions that bridge cultural and artistic boundaries, incorporating found materials and historic documents.