“Ethnographic influences in my work came through Paul Klee and Max Ernst”

An interview with Jaap Goedemoed in 2015

Jaap Goedemoed talks about the relationship between his artworks and ethnographic art. He began to paint in 1982 and after four years he started to collect ethnographic art. Four years later ethnographic influence became apparent in his work.

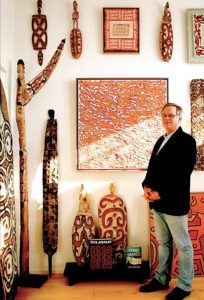

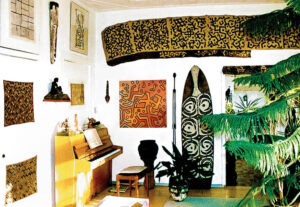

The artist in front of some of his artworks and ethnographic items from New-Guinea in his home in Amsterdam

How did you come to take up art?

I did not receive a formal art education. I had experienced different forms of art at high school where I discovered techniques such as etching and screen printing. At the time pharmaceutical studies were demanding and long, and did not offer much opportunity to produce art, but after completing my studies in 1982, I had more time and my first more serious paintings emerged. My chemical expertise facilitated my mastery of painting in oil (oil-based) and acrylic (water-based). My contacts with other artists such as Frank Lodeizen, George Degenhart and Theo Niermeijer helped me acquire additional technical skills. Spells of unemployment due to the bankruptcy of biomedical firms meant that I had some long stretches of painting. Consequently, I produced many large and labor-intensive artworks in 1996 and 1997.

Fig. 1

What triggered your interest in ethnographic art?

It began with my interest in modern art. Most classical modern artists such as Picasso, Matisse, Klee and Ernst were interested in ethnographic art and they kept ethnographic collections.

I was very impressed by the catalogue of Primitivism in 20th Century Art [Lit.1] that was published to coincide with William Rubin’s famous exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. My interest in ethnographic art was thus heightened indirectly, and it so happened that there appeared to be a good supply of ethnographic art in Amsterdam, where I live. Obviously, the masters of modern art in the early 20th century were beyond my financial scope, but ethnographic art was still within my means. Initially, I bought pieces ad hoc, I did not yet have any clear preference. Later, I preferred the more abstracted ethnographic styles, including the beautiful Kuba Cloth Shoowa Kasai Velvet (rectangular raffia palm fiber embroidery with geometric patterns) and dance skirts, and Asmat and Kamoro (Mimika) shields. Like other artists who collect arts, I am particularly interested in design and expression in ethnographic art; I am not attracted to pieces that may have been certified as authentic but are badly cut. A Salampasu woodcut in my collection was pictured in an earlier TK&C issue (publication by society of tribal art & culture): it may not be very old, but it was carved beautifully. I regard it as a contemporary piece of art.

How has ethnographic art influenced your own artworks?

From 1986, I began to collect much ethnographic art, and every week I would have a drink with collectors of ethnographic art in Ger Lambregts’ Rarekiek gallery on Prinsengracht in Amsterdam. Around 1990, there was a marked change in my works: up to then they had been mainly spatial and figurative, and rather traditional. Despite my experiments with tape and relief, my work had a strong narrative.

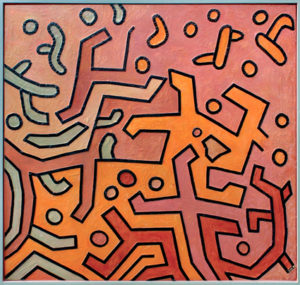

Since 1990, my works have acquired better balanced compositions on a flat surface, with frequent use of patterns and symbols; they no longer tell an unambiguous story. Others say my work has a strong ethnographic aura; the comprehensive photo of an interior accompanying this feature does indeed demonstrate that my work is in harmony with Asmat and Kamoro (Mimika) ethnographic art.

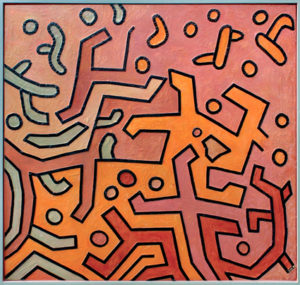

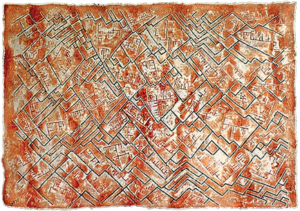

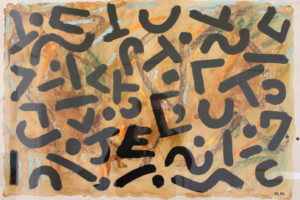

Fig. 2.

Changing tiling on a wooden plank 60x200cm (Fig. 1) may have an Escher-like motif (metamorphosis), but its execution has brought out ethnographic influences, such as the accentuated wood texture. Changing pattern with opening I 1990, 90x95cm (Fig. 2) is another artwork from 1990 and was used on the cover of my thesis. This work is undeniably ethnographic, inspired by motifs on a Ngeende dance skirt from the Kuba region. It has a distinct composition of a few lines with subtle color transitions between them. The design on a shoowa was increasingly distorted in a work from 1990: Changing pattern with relief I 1990, 100x100cm (Fig.3). After this, the influence of ethnographic art as a source of inspiration for shapes and patterns was less direct. However, several basic ethnographic influences remained: the use of various characters (letters) in all kinds of shapes, the use of repetitions, and the color scheme of mostly soft earthy colors. After 1994, I also used the so-called acrylic/gum arabic rinsing technique which means that acrylic color surfaces do not look new or homogeneous, but rather ”wornâ” or ”marked”, suggesting that they have aged, like color surfaces in ethnographic objects.

Could you explain the acrylic/gum arabic rinsing technique in more detail?

Once acrylic paint has been applied and is dry, it can no longer be rinsed off the canvas. However, it is possible if you first mix the acrylic paint with gum arabic.

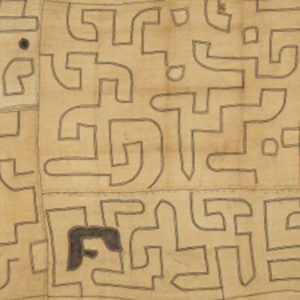

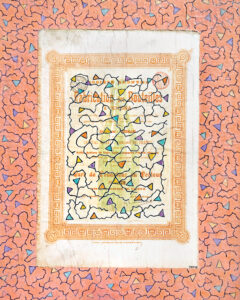

Fig. 3

After drying, the acrylic paint is rinsed off with water. If too much water is used, all will be washed off. If little water is used, it will leave more erratic acrylic remnants on the canvas. If you do not rinse at all, the acrylic/gum mixture will crackle, which also gives beautiful effects. A layer of varnish is required to seal and ”preserve” the artwork. In many of my works I opted for the rinsed version, in others for the crystalline (crackle) version, and in some of my works both techniques were applied. I learnt from Frank Lodeizen that the ”Batik” technique first requires the application of gum around the contours of the image. It is then left to dry before applying acrylic paint over the entire surface. The uncovered sections will acquire a fixed acrylic color without being rinsed off. Fig. 4, for example, shows an ancient script produced with gum arabic/acrylic, which was then wrapped in wet cloths. The result is reminiscent of an archaic manuscript.

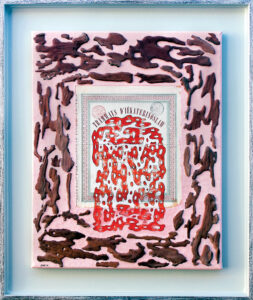

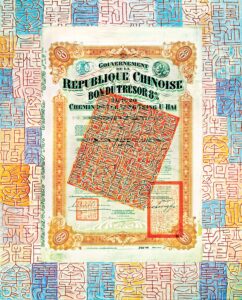

Les Tramways d’Iékaterinoslaw 2013 40 x 50 cm

Les Tramways d’Iékaterinoslaw 2013, 40 x 50 cm

Old stock paper certificates from 1897 on canvas, acrylic with gum Arabic, bark pieces off an Italian pine tree, collected in Montescudaio, Tuscany.

The red plane division in the center is based on the chips of Pinus bark I found. Other shapes of bark were used around the center pane. The red plane division looks rather ‘ethnographic’, although it was not a conscious attempt. The bark pieces in the outer part seem to lead a life of their own, as if they are circling round the inner part. In the series of artworks consisting of old stock share certificates, the outer part was usually intended as the decorative finish to the artwork, but in both this work and the work above, the outer parts seem to be competing with the inner parts. There aren’t any real connections with ethnographic art, and yet this work has an ethnographic aura due to the color scheme, the wooden bark pieces and the shapes.

This work shows how new shapes emerge in addition to the original shapes if you focus on the interspaces. Consciously or subconsciously, these ‘residual shapes’ contribute to our appreciation of the work. We see the same in many Oceanian shields.

Did you lose any of your ethnographic inspiration after these examples from 1990?

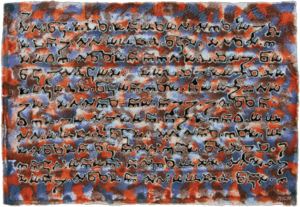

Fig. 4 – Ancient hand-writing 1997, 42 x 30 cm. Acryl/Arabic gum / modeling paste on carton. The irregularity of subtracting the acryl perfectly fits to this ancient handwriting. After some research performed after 17 years of making this artwork, it appears that that this word text is part of an old Samaritan handwriting from the 13th century BC. The text part refers to Genesis 21:4-14. The manuscript is kept in the Chester Beaty Library in Dublin.

I don’t think so. After my first encounter, my enthusiasm for ethnographic art was obviously at a peak, as was my tendency to create inspired applications. However, there were also other influences, such as computer designed plane divisions, regular polyhedra, especially convex pentagons which form isohedral tilings, patterns that our brain cannot produce. They were of interest to Douglas R. Hofstadter, known for his book Gödel-Escher-Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid [Lit.2]. You will find one such basic pattern in many of my works.

Other influences are the beautiful patterns in nature, such as the wonderful pigmentation patterns of tropical seashells, for example Oliva porphyria L. These patterns are described by the researcher Hans Meinhardt [Lit.3]. It is interesting that patterns such as those of tropical seashells are not part of the ethnographic cultural expressions of indigenous Oceanic peoples. Apparently, Westerners (see Fig. 5) see them differently than indigenous people, and Oceanic inhabitants are less inclined to be inspired by beautiful natural designs, although we might have expected otherwise. The wealth of well-known and unknown manuscripts from ancient cultures have been an additional source of inspiration, and of course other artists’ works can also be influential, at least if they also have an ‘ethnographic feel’.

Fig. 5 – Division of the plane no. II 1997, 58 x 42 cm. Acryl/Arabic gum on paper. The subtraction treatment with wet textiles adds an additional value to the surprising patterns of the black lines and smaller red patterns.

It may not be surprising that I have collected quite a lot of Frank Lodeizen’s works. His abstract works reminded me very much of ethnographic compositions. When he came to my house and saw my Kuba canvases and other ethnographic work, he was very surprised. He was clearly unaware. It was quite interesting. It means that he probably acquired his style, which is now considered ‘ethnographic’, by closely observing and absorbing Klee’s and Miro’s works and those of similar artists. He didn’t strike me as somebody who had archives of artistic patterns and motifs, because his art must be ‘spontaneous’. I think that the influence of ethnographic shapes on artists after 1945 has been much greater than many would think possible: the secondary influence should not be underestimated, although not all artists are aware of the origin of their style.

Incidentally, many of my patterns are also my own designs, often created with a pencil and a sketchpad during times of relaxation when on holiday, and through shapes that presented themselves in my surroundings.

Furthermore, my most recent work (shown in the opening photo with the artist), 100x100cm was created between September and December 2014. Once again it is closely related to Asmat shields: I used natural material (bark pieces that had fallen off Pinus Pinacea trees in Tuscany), an almost identical simple color scheme (white-black-brown to ocher, with an additional orange red hue in my work), and with a strong relief. Of course, my work is completely abstract, whereas Asmat shields are about stylized symbolic representations. I think the beautiful Mimika shield next to it should however be considered as an entirely abstract art. Coincidence arising from the irregular shapes of bark pieces is important in my work. In Asmat patterns coincidence hardly exists: their patterns are passed on from generation to generation. It would be interesting to see how Asmat and Mimika woodcutters would respond to my work.

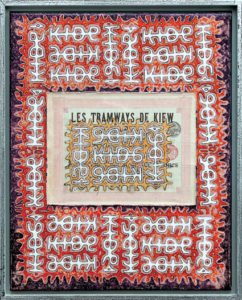

Les Tramways de Kiew 2013, 40 x 50 cm.

Old stock paper certificates from 1905 on canvas, acrylic with gum arabic.

This is an example of recent work with many symbols and signs, and much repetition. In Africa and Oceania repetition is standard in any form of art, such as music, stories, visual arts, dance (with masks). The ordering of the symbols and signs shows an irregular regularity. Symmetrical, but not quite: it is a little trick applied by many indigenous artists in Oceania and Africa. They know that too much regularity is predictable and therefore boring.

Jaap: ”I still remember the Asmat shield in the Volkenkundig (ethnological) Museum in Rotterdam (now called Wereldmuseum – world museum) that contained the imprint of a Western boot having become part of traditional Asmat patterns. The designer clearly regarded the imprint as a contemporary and interesting design. Here you see a similar process: I happened to find a 3D ‘KIDS’ label which was a source of inspiration, it needed a bit of manipulation. Look, doesn’t it remind you of an Asmat shield pattern, although it was not intentional.”

Les Tramways de Kiew 2013, 40 x 50 cm

Why did you choose to have those two books in the opening photo?

I recently read Carl Hoffman’s latest biography Savage Harvest, and it made a deep impression on me. Michael Rockefeller, a young anthropologist, was very young when he investigated the cultural expressions of authentic indigenous peoples with a passion. He was probably a few miles off the coast of New Guinea when he hit seriously bad weather (in November 1961) in a rickety catamaran that was not seaworthy. His boat capsized. After strapping an empty petrol can to his torso, Michael decided to swim to the distant shore many miles away, while his Dutch escort was left with the capsized catamaran. It was extremely bad luck that Michael landed on the territory of an Asmat village. The people were no longer ‘allowed’ to take revenge after a ‘headhunting’ spree by a neighboring village. And not only that, but they had lost five tribal members during ‘corrective’ action carried out by a Dutch patrol. And then this ‘white man’ (whom they probably already knew from his previous visits to collect objects) suddenly appeared from the sea like Neptune, all alone and without any guards, exhausted after having swum 18 hours. It so happened that a group of Asmat warriors from the village of Otsjanep were having a rest on the beach. The Asmat warriors probably pierced Michael with a spear the moment he set foot on the beach, his head was severed from his torso and roasted on a fire, the contents were consumed, ‘sucked off a sago palm leaf’. [Lit.5] The young Rockefeller story is so tragic, he who was so eager to come up with something special and show it to his domineering father. And it looked like he had found it on his expeditions to the last indigenous peoples on our planet. It is described in ”Primitive Art” and demonstrated in his collection of ethnographic art for the newly opened Museum of Primitive Art in New York. It is amazing how he managed to gather such a large collection on his own when he was only 23 years old [exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York]. The descriptions in his book are quite revealing when he relates how he purchased some very large and impressive Bis poles for next to nothing in the very village of Otsjanep. Someone who can buy Bis poles must be very powerful in the eyes of the Asmat, and therefore, from an Asmat perspective, the consumption of Michael’s life forces was seen as compensation for previous Asmat losses suffered during action carried out by the Dutch patrol.

The book also explains the reasons why Dutch administrators and mission members were keen to present Michael Rockefeller’s death as a tragic drowning incident, and not as an expression of cannibalism: The Netherlands was under great international pressure to renounce Western New Guinea in lieu of Indonesia and it sought support from America (which made no difference). If the outside world had heard that there was still headhunting and cannibalism, it would not give a good impression of the Dutch administration in the region. And the Rockefeller family was an influential family in the US, not to be ignored. There is evidence that the Dutch administrators and mission members had been made aware of Michael Rockefeller’s true tragic end almost immediately, but they were ordered by a higher authority ‘to keep it under wraps’. Even today, Dutch archives remain closed.

I couldn’t get the story out of my head, and I therefore also bought the travel account of Michael Rockefeller’s expeditions [Lit.6], published in 1967. I noticed that this book now is a collector‘s item on the internet where they ask high prices. It is fascinating to know that this book contains many photographs of Otsjanep and its villagers, possibly including the warriors who killed and cannibalized Michael Rockefeller. As a kind of tribute of honor, I have displayed the book The Asmat of New Guinea: The Journal of Michael Clark Rockefeller (The Michael C. Rockefeller Expeditions 1961) in the opening photo.

Composition 2014, 100 x 100

Composition 2014, 100 x 100 cm

3D artwork with pieces of Pinus Pinacea bark (‘umbrella pine’) from Tuscany.

This time the bark pieces have a light orange brown color. One of the bright orange shapes was an original chip of bark off the Pinus tree with this kind of ‘eye’. It is still possible to identify this piece by its grain structure. All the other bright orange pieces were copied and cut out of cardboard. It has created a strong sense of rhythm between the tree bark structures and the smaller shapes in bright orange. When taking photos after 11 am as sunlight falls diagonally and partly across the artwork, the artefact comes to life. The bark pieces in the sunlit part have much more depth and seem to be jumping off the flat surface, and the white background (titanium acrylic paint mixed with sand) emanates a brilliant white.

You seem to be particularly attracted to abstract ethnographic art. Why?

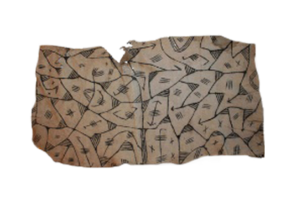

Fig. 6 – Mbuti tapas from the Ituri wood in Eastern Congo.

Considering that some indigenous peoples experienced a very different economic development to Western societies, it continues to fascinate me how their artists allowed their design and artistic expression to transition into abstraction with much greater ease than artists in our Western society. In the West, abstraction only really took off in the 20th century, meanwhile some of the previously mentioned shoowas have been part of European collections or museums for centuries (since the 17th century). They obviously did not initiate change at the time. European artists were clearly not receptive to this kind of change.

Earlier, I mentioned the beautiful abstract pattern on the Mimika shield next to my artwork in the opening photo. Undoubtedly, we now see this ethnographic art through ‘Western eyes’, and the entirely abstract pattern on the Mimika shield, is more likely to strike a sensitive chord in us today than the stylized symbols of Asmat ethnographic art, although they are very beautiful too.

A Mbuti tapas loincloth [Fig.6] from the Ituri region of Congo also has abstract patterns. The plane division is beautiful with only a few repeating basic elements. I have had this tapas for about 30 years and it is most unfortunate that I did not give it the interest it deserved. In Ger Lambregts’ gallery on Prinsengracht, Amsterdam, you could buy such tapas for 100 guilders (about 45 Euros or 50 dollars) in the 1980s, which is a rather small sum for such beautiful cultural heritage, which may soon be lost. I’m afraid I was not much aware of the value at the time, otherwise I would have bought more. A tapas is made by men out of a mixture of bark from six different tree varieties, the women would make the color pigments (only black in this tapas) and produce the images. The pattern will most likely be an abstracted representation of something typically found in the dense rainforest. We have many samples of transitions in Mbuti tapas from abstract, to semi-abstract and figurative. It is amazing that these semi-nomadic people can produce such sophisticated pieces of art in such a humid climate and such a harsh environment, where no other peoples other than a few of these Pygmy communities can survive. They may have been making these abstract images for hundreds of years. If Paul Klee had seen these Mbuti drawings, they would have probably inspired him greatly. The fusion of special plane divisions with some rather dreamy or poetic elements, based and built on simple lines and the importance of symbols and signs, they are all typical Klee features. It is a pity that the Mbuti tapas had not yet emerged from the Ituri woods during Klee’s life because they would have had an impact on Klee and history of art. Mbuti were copied by several other artists, such as Jasper Johns and his crosshatch method, but the artworks are less refined and lack the poetry of the Mbuti and Klee, and some are imitated without much forethought and without any original artistic input. Unfortunately, it often happens to inspiring ethnographic examples: they are followed blindly. Even the masters of modern art in the early 20th century were aware of this danger and might consequently suddenly stop applying ethnographic elements in their works.

It is quite amazing that we have these harmonious and peaceful Mbuti presentations on tapas, created by different indigenous groups in the same Ituri region, and that the fiercest polychrome masks I have ever seen came from the same region, some of which I have included in my collection. [Fig.7] They are so intimidating that my family members objected to having them on the wall in our living room.

Fig. 7 – Polychroome mask from the Ituri wood.

Have you visited Africa or other countries with ethnographic art?

No, I’m afraid not. Due to my interest in Egyptology, I have visited Egypt, but I have not been to ‘Dark Africa’. Dropping down the wide Congo River must be the most wonderful experience. I hope I will get round to it one day. Currently, the rediscovery of those three Mayan cities of Chactún, Lagunita, and Tamchen in Campeche, Yucatan, Mexico is in the news. There are some beautiful photos taken by the expedition leader, Ivan Sprajc, on the internet [Lit.4]. They reminded me of my own photos from 1989 (Fig. 8), when I visited the Mayan ruins of Bonampak and Yaxchilan in nearby Chiapas with guides. Both sites were overgrown by the jungle. Yaxchilan can only be reached by boat over the Usumacinta River and Bonampak after a long trek on foot through the Lacandon jungle. At the time both sites were guarded by Mexican soldiers to prevent looting. The constructions and sculptures in Yaxchilan and the murals in Bonampak were stunning. The expeditions to these Mayan sites in the jungle were a great experience!

You are now 59. What else would you like to achieve in relation to your artwork?

Fig. 8 – Maya ruins and at the foreground stele in Yatchilan, Mexico, december 1989.

So far, my artistic oeuvre has developed over a period in a series of waves: 1984-1985 saw an end to figurative work and I was open to multicultural influences. Around 1990 there was a transition period to larger abstract works, and around 1997 I produced large, multicultural mosaics. They were followed by a quieter phase in which the substrate consisted of old stock paper certificates. It was a beautiful collection. This relatively quiet phase was also related to more demands on time due to work and family life. Gradually, I am finding that I have more time available to create art and I would like to produce some more larger works. I would like to apply the experiences and techniques I have acquired over the years: the acrylic/gum rinsing technique and the use of special materials such as Pinus Pinacea bark pieces and old documents. I imagine my future works will retain an ‘ethnographic aura’, which has become part and parcel of my being.

Postscript

At the time of the interview in 2015, there was much discussion about ethnographic influences that might have shaped certain artworks, including the work Changing pattern with opening I 1990, 90x95cm (Fig.2) from 1990. At the time, I was unable to illustrate this influence with an attractive sample of woven raffia from the Kuba region, and the influence was dispelled in a few words. However, 28 years after creating the artwork, I was surfing on the web and noticed this attractive sample on the site of an ethnographic art dealer in San Francisco! The connection and source of inspiration are obvious; I knew I had seen these specific shapes before.

Detail of Kuba Noblewoman’s Skirt, Bushoong Group, DR Congo, Early 20th century, Raffia palm fiber, appliqué and embroidery, 89×482 cm

Changing pattern with opening I 1990

My use of color gives my artworks quite a different character compared to the canvasses of Kuba artists, which are usually sandy colored. As I said before, there is a very direct ethnographic influence around 1990, and although we still see the same influence in larger works after 2010, which have increasingly become 3D, it is not as easy to identify the influence in a specific example compared to the example above. The artwork from 1990 was used on the cover of my thesis Polyphosphazene Drug Delivery Systems for Antitumor Treatment, 28 June 1990. I gave the artwork in the thesis the title ”Drug release and polymer degradation struggles”. The lines in the artwork remind many people of Keith Haring’s work. However, as far as I know, Keith Haring did not produce any abstract artworks in this way.

Translation: Rosemary Mitchel-Schuitevoerder

Literatuur:

Lit. 1: Primitivism in 20th Century Art, Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Edited by William Rubin, Volumes I & II, ISBN 0-87070-518-0, 1984.

Lit. 2: Metamagical Themas, Questioning for the Essence of Mind and Pattern, Douglas R. Hofstadter, Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, New York, ISBN 0-465-04540-5,1985, p. 191-212: Parquet Deformations: A Subtle, Intricate Art Form.

Lit. 3: The Algorithmic Beauty of Sea Shells, Hans Meinhardt, Springer Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York, ISBN 3-540-57842-0, 1995.

Lit. 4: Photos: Scientists Found Three Lost Mayan Cities in the Mexican Jungle, with photos made by Ivan Sprajc, http://www.ryot.org/lost-mayan-citieschactun-lagunita-tamchen/791177.

Lit. 5: Savage Harvest – A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller’s Tragic Quest for Primitive Art, Carl Hoffman, William Morrow/Harper Collins Publishers, 322 pagina’s.

Lit. 6: Gerbrands, Adrian A., ed. The Asmat of New Guinea: The Journal of Michael Clark Rockefeller. New York: Museum of Primitive Art, 1967.

…

2015, Alexander Kamyshin during his visit in Amsterdam

For several years a fan of the stock paper artworks – living in or near Kiev – put an interview with the artist and some artworks on a website, at that time on URL www.scripokiev.com. The website was ‘on air’ from 31 January 2010 to somewhere in 2014. With ‘scripo’ is meant ‘scripophily’, i.e., the interest in collecting old documents like stock papers, bonds, bank notes, etc. The artist came into contact with this art fan when he left a message on the artist’s website with appreciating words.

The name of the art fan was Alexander Kamyshin. By mail he forwarded questions to the artist, and with the artist’s responses and some pictures of artworks sent by mail he composed an interview on the website of Scripophily.

By chance he visited in 2015 Amsterdam on a business trip. On the picture above it can be seen that Alexander visited the artist in his home.

The interview in Russian language as it was present on the scripokiev website is given in the next article.

…

Общество „Кіевскій СкрипофилЪ“

Старинные акціи и облигаціи

Вторая Жизнь Старинных Ценных Бумаг — Жизнь в Искусстве

Дорогие скрипофилы, как и обещали, публикуем интервью с человеком, связанным со скрипофилией. В нашем фокусе — человек от искусства, чьей музой и полотном стали старинные ценные бумаги. Если вы дадите ему акцию или облигацию, он изменит ее до неузнаваемости, в то же время оставив оригинальной и прекрасной. Этот человек — художник в теле медика — Джаап Годемод (Jaap Goedemoed), Амстердам, Нидерланды.

— Джаап, расскажите, пожалуйста, нашим скрипофилам о том, что именно Вы делаете с ценными бумагами, про Ваш стиль.

— Я начал заниматься живописью в начале 80-х годов. Сначала я писал маслом, потом акрилом, и все время экспериментировал с основой — использовал льняне ленты и пасту для моделирования. В 90-х годах я перешел к абстракционизму, во всех моих работах есть сильный акцент на деталях, я стараюсь добиться того, чтобы на работы было интересно смотреть издалека как на структуры, геометрические формы; и вблизи — детали тоже очень важны.

Сейчас я использую как акрил, так и гуммиарабик (этой технике меня обучил мой друг, художник из Амстердама Франк Лодизен (Frank Lodeizen). Основа моих работ — открытые и закрытые структуры, состоящие из множества элементов, выполненных из фрагментов газет, старинных банкнот, старинных тосканских налоговых чеков, японских оттисков, оригинальных рукописных исламских текстов, старинных ценных бумаг наконец:)

— А когда к Вам пришла идея использовать старинные акции и облигации в своих работах и какие именно ценные бумаги представляют для Вас интерес?

— В 1994 г. я провел отпуск в Тоскании, в маленьком селении под названием Монтескудайо (Montescudaio) вместе со своим другом, Франком Лодизеном (Frank Lodeizen). Я нашел на заднем дворе дома, где мы жили, старинные налоговые бумаги времен Муссолини (1919-1944 гг.). На моем вебсайте Вы можете увидеть множество работ, в основу которых легли эти бумаги. Так родилась идея использовать старинные бумаги в моем творчестве. Кстати, с тех пор я часто отдыхаю со своей семьей на вилле в Монтескудайо (Montescudaio), люблю это место.

Затем чисто случайно я увидел в антикварной лавке в Амстердаме старинные ценные бумаги периода 1890-1930 гг. Меня особенно привлекают бумаги городов таких как Одесса, Киев, Днепропетровск, Саратов, Грозный, Екатеринослав, Донецк, Санкт-Петербург и т.д. Трамвай Екатеринослава – какое великолепное название!

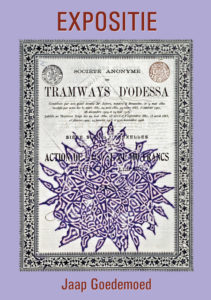

— Вы сделали целую выставку работ под названием «Tramways d’Odessa». Расскажите нам подробнее об этой выставке.

— Конечно, с удовольствием расскажу. Выставка «Tramways d’Odessa» проходила в амстердамской галерее Руимте (Galerie Ruimte) с 27 Апреля по 18 Мая 2008 г. В основу выставки легли работы, выполненные с ценными бумагами времен 1880—1930 гг. Я декорировал бумаги новыми символами, в том числе и этническими, старался придать им новый образ, вдохнуть вторую жизнь, так сказать:)

Было выставлено 52 работы и 4 постера, в том числе 11 работ с ценными бумагами, которые я сделал в период 2005-2008 гг., а также мои предыдущие работы, начиная с 1990 г. Работы были оценены от 750 до 1750 евро, в зависимости от сложности и количества деталей.

Я очень люблю работать с большим форматом, отдельные элементы выполнены акрилом и гуммиарабикой, шелкотрафаретной печатью на канве, ценных бумагах и документах, дереве, стеклянных бутылках, как бы приглашая зрителя подойти ближе.

— Джаап, признайтесь, Вам хотелось побывать в Украине и России, родине Вашего вдохновения?

— Конечно! На самом деле я был в Украине в 1992 г. был в Одессе, Крыму, Киев, к сожалению не успел посмотреть. Затем я отправился в Москву и Санкт-Петербург. Многое, наверное, поменялось с тех пор…

Эти страны интересны мне и с точки зрения рынка продажи моих работ.

Однако пока это скорее планы, чем реальность.

— Да, наша страна сильно пострадала от финансового кризиса и людям необходимо время для того, чтобы возобновить платежеспособность. Джаап, расскажите о Ваших планах на будущее.

— Больше работать. Пока мне не удается посвящать достаточно времени моему искусству. Я работаю фармацевтом в RIVM

(Dutch Institute for Public Health and the Environment) и

разрываюсь между ежедневной работой и работой для души.

Искусство — ключевое в моей жизни. Верю, в конце концов мало что останется от моих фармацевтических отчетов, исследований и патентов. А полотна останутся.

Беседу вел Александр Камышин специально для Общества „Кіевскій СкрипофилЪ“.

Posted in Трамвай, Интервью, Одесса

January 31st, 2010

Читайте также:

Севастопольский Трамв ай — История Глазами Скрипофила

Киевский Трамвай — Финансовая Сторона Истории

…

Early 1991 various art works of the artist were on the walls of biomedical company OvaBloc Europe B.V. in Leiden, The Netherlands. The valuation was written on behalf of the insurance of the art works. Jan Pieter Glerum (1943-2013) was a well-known art & antique expert and auctioneer (Sotheby’s 1974-1989, Amsterdam Auctioneers Glerum 1989-2007), and later a Dutch television personality.

…

A serious piece of art on my wall

On Saturday 22 February 2020, a feature about my purchase of a first piece of art was published in My favourite item in the Dutch NRC newspaper. I submitted 680 words and some photos, but I had exceeded the word limit of 240 words for this regular feature. Despite some deletions, Gretha Pama, the editor, wrote a good article. I will post the longer version on my website and add several interesting facts about the Dutch artists Lucebert and Frank Lodeizen.

Although I had the third-highest academic grade in my peer group, it took 7.5 years to complete my long uninspiring studies of pharmacy (currently it is a five-year degree course) in the northern student city of Groningen. It was a long way from Amsterdam, and rather parochial in the 1970s. After receiving my degree, I returned to the west of the country, where I hoped I would experience some cultural rejuvenation. I had found a job at a pharmaceutical company between Amsterdam and Haarlem (immediately west of Amsterdam), and I could not have wished for more attractive living quarters in Amsterdam: for one year I was the caretaker of a beautiful floor in an old historic building on the Amstel river, diagonally across from the famous theatre Carré, not far from the sluice gates in the Amstel.

I had only recently taken up painting again and I was still quite a novice. I did not yet have my own style and was not quite sure of the purpose of my painting. I was rather guileless and believed that my paintings should exude a ‘strong message’: ‘we had had enough of all that woolly art!’ I hung several paintings with strong messages, or should we say ‘shocking messages,’ from the 1980s on the walls of my beautiful studio. At the time I did not realize that a brazen message that sticks out a mile does not necessarily support the artwork.

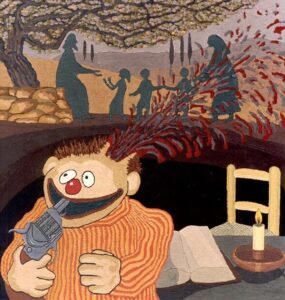

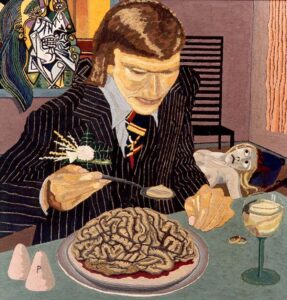

1980 Reaching out to the Lord – oil on board, 80x80cm

1980 The hungry bridegroom – oil on board 80x80cm

Looking back, I realize that the twenty-four year old Jaap was out to shock the socks off his audience. The painting on the left shows Ernie (in the children’s programme Sesame Street) who suits the action to the word in the biblical text: “But Jesus called the children to Him and said, let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these (Luke 18:16). Ernie depicts the artist’s rather cynical religious experience. The scene in the background was taken from ten-year old Jaap’s Sunday school booklet; I was sent to Sunday school every week to learn about the Bible. Of course, this was great for my parents, because it took me off their hands for a couple of hours. Religious education did not have much effect: when I became an adolescent, I unwaveringly decided that religion was a figment of the mind, based on a human need to control the fear inherent to life. It does not offer consolation to people who are not interested in such fantasies; throughout the ages, religion has proved to be incapable of reducing worldwide acts of terror. Religion does not have a positive influence on man.

The painting on the right might be perceived as even darker. It looks as if the marriage only lasted a day. Obviously, I was interested in Picasso’s work at the time, although I did not yet know that Dora Maar, a fascinating artist and photographer, modelled for the ‘weeping woman’. Did you notice the woman’s lock of hair draped over the edge of the painting? Just a little joke. The black ladderback chair in the right-hand corner is a version of the Hill House 1 Chair designed in 1903 by Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Younger friends, visiting me at the time, thought the works were ‘cool’ or whatever they said in 1982. However, the older generation, like an older auntie of mine, was rather shocked by these paintings and wondered whether I was in my right mind. After I had produced several such paintings, I had got it out of my system and could move on. I found that after a while you tire of shocking messages, you lose interest in those works of art, they have a limited shelf life. The twenty-four year old Jaap had not yet shaken off adolescence, but in the following years his techniques and themes showed great progress. Ten years later – in 1990 – the adolescent/painter had completed his experiments, and the mature painter had acquired a personal style, a typical Jaap Goedemoed style, still apparent in my current work.

After the oeuvres from the 1980s were taken down, I decided that it was time to have a serious piece of art on the walls of my new home in Amsterdam-Zuid, an upmarket quarter of the city. After all, my pharmaceutical job provided me with enough money and as a bachelor I had no expenses generally associated with family life. In 1984, I decided to have a browse in Galerie Espace on one of the canals, Keizersgracht; it was the last day of an exhibition of Lucebert’s paintings.

Lucebert (1924-1994) is a well-known artist in the Netherlands; initially as an innovative poet, ‘the Emperor of the Fifties’, and as a visual artist. He knew the painters of the international Cobra movement well, but he never joined the movement. Although his artwork do not fetch as much in the international art market as work by Appel, Corneille, Constant, Alechinsky, and Jorn, his paintings are nevertheless quite pricey. Lucebert had many exhibitions abroad.

Many of his works in the gallery, the larger oil paintings, did not fit my budget. There was a smaller piece of art (72x82cm) on the first floor of the gallery that was not in a prominent place. It had apparently not drawn much interest as it was still for sale. Although I felt it was slightly over my budget (7,250 guilders ~ 3290 euros), art purchase arrangements at the time allowed me to pay in instalments over a period of thirty-six months which made it feasible. The assistant in the gallery who served me, looked at me in surprise, probably thinking ‘strange for such a young person’ to spend so much money on art – I was a young-looking 28 year old –, or maybe she was wondering how I could make such a decision in a matter of minutes. Later I discovered that the young lady was Maia Swaanswijk, the artist’s daughter (Lucebert’s real name was Bertus Swaanswijk), who managed sales in the gallery.

Very soon the painting ‘Mother wins’ was given a permanent place in my new home, and it has not been moved for 34 years. After all those years the painting still fascinates me, and I have never regretted the hasty purchase. This piece of art really appeals to me because it not only shows the typical jagged unpredictable Lucebert forms of heads and bodies, in black and dark purple outlines, but it also has many soft pastel shades.

Lucebert 1984 – Mother wins, oil painting on canvas, 72x82cm

It is this combination that makes the painting so strong and appealing to me. According to Wim Hazeu, his biographer, Lucebert was colour-blind. There are many of Lucebert’s paintings I do not like: too many harsh colours on top of each other. Sometimes a painting needs lighter and softer colours for more balance to create quieter sections that bring out other parts in the artwork.

I am not sure about Lucebert’s colour blindness: for example, I love the colours (and the composition) of his gouaches in his beautiful poetry publication Van de maltentige losbol.

The empty wall around Lucebert’s work of art has changed significantly over the past thirty-four years. In the immediate years after the introduction of Lucebert’s work, the wall around the painting, and the mantelpiece were filled with ethnographic objects (masks and statues mainly from Africa), predominantly collected in Amsterdam. I liked the combination of Lucebert’s painting and ethnographic art, and his painting held up well among all the ethnographic busyness.

Apparently Lucebert did not approve of ethnographic art, he would not buy or collect it because he did not want ‘ethnographic art removed from its cultural context’. I did not share his sentiment, my urge to collect was based on my feeling or awareness that all these beautiful cultures and their expressions are disappearing across the world and just to have several of these cultural expressions in my limited living environment gives me great comfort. Unfortunately, ethnography is no longer available in Africa and can now be seen mainly in collections and museums in the West. More than eleven years after hanging up Lucebert’s painting, my wife was sharing the living quarters with me, we had children, and inevitably the ethnographic content in the living room was reduced after we moved it to our upper floors. Only Lucebert could stay, and gradually found himself in a more ‘gentrified’, much emptier living room among many interesting objects.

1996 Jaap’s living room – The Lucebert painting surrounded by more and more ethnographic items

2013 The family living room and the Lucebert painting amidst a reduced number of ethnographic items

From 1990 to 1996, I collected many works by another artist well-known to Lucebert. In the early 1950s they would meet in the café frequented by the Cobra artists (Café Eijlders in Amsterdam), they became good friends and in February 1952 they travelled to Paris together. This artist was the aforementioned Frank Lodeizen, whom I will feature in more detail. Frank had not shared the same degree of success that was enjoyed by Lucebert and the Cobra artists for a variety of reasons. I got to know Frank’s work well and appreciated the beauty and sensitivity of his work from the period between1986 and 1996. And because Frank had not been successful in the art market, I had been able to buy some of his beautiful paintings at very reasonable prices, including 29 unique pieces of art. Later I added 48 reproductive works (etchings, lithographs, prints, lithographs, screen prints). Coincidentally Frank Lodeizen’s early works included two portraits of his friend Lucebert.

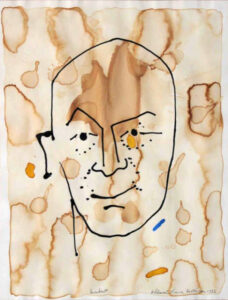

1957 Portrait of Lucebert Woodcut

1992 Portrait of Lucebert on paper 27x35cm

The portrait on the left is beautiful, consisting of just a few black lines and dots, and some coffee stains, and several touches of brown, and a little dash of blue. And although I don’t know why it is there, it adds interest to the work. The portrait was created on 6 February 1992, and Lucebert had probably lost his hair due to cancer and chemotherapy. Jaap added the portrait to Frank Lodeizen’s best pieces of work and soon it became a feature on my living room wall.

Shortly afterwards (in October/November 1993) I bought a second Lucebert portrait made by Frank Lodeizen: a woodcut like Lucebert’s portrait from 1957. I have already described how my first ‘expensive’ art purchase was an oil painting by Lucebert in Gallery Espace in 1984. To me it was a miracle how I acquired two portraits by Lodeizen, one of the young Lucebert and one of the older and by then sick Lucebert. I was very grateful to have them, and the portraits were not any old portrait, I regarded them as my cultural heritage and I was aware how privileged I was to have come across these pieces of art and could even purchase them.

In June 1995 I bought a third piece of art associated with the relationship between Lucebert and Frank Lodeizen. This is the work of art from 1994, Lucebert’s funeral, mixed media on paper, 100x70cm. If you study it closely, you will recognise the random letters of LUCEBERT in the abstract, although the letters B and R are missing. It is a strong piece of work, and it complements the memory of Lucebert, together with the two Lucebert portraits made by Frank Lodeizen.

1994 Lucebert’s funeral, mixed media on paper, 100x70cm

Frank Lodeizen and Lucebert were close friends, who frequently met in the early 1950s, and possibly once a year in the 1980s and 1990s. As an eleven-year old boy Frank Lodeizen managed to survive the Holocaust by escaping from the roundup of Jews at Central Station, who were waiting to be transported to Westerbork in the east of the Netherlands, a detention and transit camp. His mother and stepfather, and his sister, and many other relatives died in Sobibor, an extermination camp in Poland. Lucebert died of colon cancer in May 1994; Frank Lodeizen died in 2013. Frank attended Lucebert’s funeral in Bergen (the Netherlands) on 16 May 1994. Frank was deeply moved when Lucebert died. In his collection of Tuscan letters (1994), Frank wrote the following lines dedicated to Lucebert, which show us how important Lucebert was to Frank Lodeizen.

Lucebert the unspoken human cry

invisible pillar of support

your poetry will never die

it has given us a new consciousness

floods of expression enshrouded in warmth

for whoever can feel

reality seen through the mirror in your drawing

cheerful and sombre poetry

your paintings yin and yang in harmony

light and airy but filled

Wim Hazeu’s biography of Lucebert was published on 6 February 2018. Not long after, big headlines in all the Dutch newspapers reported the disclosure of Lucebert’s letters which he had written when he was a young man living in Germany (Apollensdorf near Wittenberg, where he was employed in an ammunition factory). It appeared that the young Bertus Swaanswijk (which was his real name, and he did not change it to Lucebert until after 1945; his father’s first name was Lubertus; ‘Luce’ and ‘bert’ both mean ‘light’) had volunteered to work in Germany in June 1943, and in his letters to his girlfriend Tiny Koppijn, the young Swaanswijk clearly expressed himself pro-Nazi; in fact, his expressions were anti-Semitic and he ended the letter with the ‘Sieg Heil!’ greeting. Lucebert never referred to this aberration at any time in his life. It led to much criticism, particularly because Lucebert had always presented himself as a revolutionary, against (colonial) rulers, against evil and unfreedom, and because he took issue against many people with reactionary views and narrow-minded citizenry. Of course, Lucebert knew that this publication would be the end of his status as the front-runner of the Vijftigers, a group of experimental writers loosely connected to the Cobra artists, and of his artistic career. Many of Lucebert’s fans say that Lucebert’s approach and commitment to life after 1945 made up for his youthful indiscretion. Some of Lucebert’s followers believe that Lucebert’s image was damaged, that much of his moral authority now was lost, and that some of Lucebert’s poems can now be read from two different perspectives.

Lucebert had always been Frank Lodeizen’s shining light, Frank Lodeizen had wanted to be like him, and play with language and words as well as paint. Because these revelations about Lucebert were not made public until 2018, Frank Lodeizen did not see his great hero fall from his pedestal.

It is interesting to reconsider my purchase of works of art retrospectively: first there was my rather impulsive purchase of a relatively expensive work of art by a well-known artist (Lucebert oil painting 72x82cm, 7250 guilders (~ 3290 euros), a painting by an established artist. It was followed by many purchases of art by an artist who was less successful in the art market: 31 works of art (29 unique items) by Frank Lodeizen with a total cost of 11,642 guilders (5,200 euros) (approximately 370 guilders (on average 170 euros per work of art). In comparison, the latter were higher risk purchases of works by an artist who was not established. All in all, Frank Lodeizen’s works of art have greatly influenced my life and my development as an artist. I treasure my possession of the Frank Lodeizen collection, it reflects a typical phase in my life with memories of the interactions between the artist Frank Lodeizen and me. Whereas I regard Lucebert’s painting as a powerful work of art, it remains “the painting on the wall” without any added effect on my artistic development. I did however buy many collections of and about Lucebert’s poems, and many books of and about Lucebert’s paintings, which fill a bookshelf, but that’s all. In retrospect, it was a blessing in disguise for my own artistic development that I then became fascinated with Frank Lodeizen’s work and that I did not buy a second ‘expensive’ Lucebert painting! In terms of financial investment, a second Lucebert painting would have been better, but as a ‘human’ investment in myself, my choice of the ‘unknown’ Frank Lodeizen artworks turned out to be the best pathway for me.

Oct 2017, At the artist’s home. The recently made sea balls composition (150 x150 cm) on the wall

At the artist’s home in 1996. Ethnographic influences

Hello Your mode of describing everything in this paragraph is genuinely good, every one be able to effortlessly know it, Thanks a lot. Thank you.

Thanks for conveying this particular message and rendering it public.

It is best to take part in a contest for among the best blogs on the web. I’ll advocate this web site!

Hi there! This post could not be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept chatting about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me & my neighbor were just preparing to do a little research on this. We got a grab a book from our area library but I think I learned more from this post. I am very glad to see such great info being shared freely out there.

Very interesting details you have observed, thank you for posting.